And as a corollary, frugality does not mean deprivation, suffering, or unhappiness.

Spending more does not equal more happiness just as spending less does not equal less happiness. While frugality is core to how we achieve FIRE, it does not have to mean a life of deprivation. The FIRE community is too creative for that.

[This post was significantly revised and published in Simplify Magazine (June 2025). The updated post can be found here]

Setting the Stage

Recently many FIRE content creators have espoused the view that the FIRE movement has recently “evolved” from deprivation, driven by extreme frugality to, now, increased spending on stuff we “value” somehow causing increased happiness along the way. (“I like expensive cars, so I should buy a new expensive car since I VALUE expensive cars and now I am happier” — at least until the shiny newness wears off.)

Definition of Deprivation: “the fact of not having something that you need, like enough food, money, or a home; the process that causes this

- neglected children suffering from social deprivation

- sleep deprivation

- the deprivation of war (= the suffering caused by not having enough of some things)” – Oxford Learners Dictionary

That deprivation-to-value narrative should not be conflated with an unhappiness to happiness narrative.

As Mr. Money Mustache’s (aka Pete Adeney), Vicki Robin (author of Your Money or Your Life), and many others have long demonstrated that frugality while pursuing FIRE does not have to mean either deprivation or unhappiness.

Pete and Vicki advocated for finding contentment in “enough.” Pete did this while living on less (~$25K a year with a paid-off house). He didn’t (and doesn’t today) live a deprived or unhappy life. Pete and many other FIRE content creators since 2013 have demonstrated replicable, creative ways to spend time with family, stay healthy, commute, eat well, etc. without spending a lot of money.

Frugality Increases Happiness

I realize this may sound counterintuitive (especially with the marketing world trying to convince us otherwise), but I have found that spending more does not lead to increased sustained happiness, while spending less frequently does lead to increased sustained happiness. How could that be?

There are three main reasons for this surprising truth:

Main Thing #1: I can usually get or do essentially the same things for much less

Frugality is the superpower of FI. It is the core that enables us to create margin that we can use to pay off debt, save, and invest. Even a high-earner making $400K+ has to reign in spending or risk having a low net worth, as well illustrated in Thomas J Stanley’s book The Millionaire Next Door.

Cutting back on spending does not mean that we have to live a life of deprivation. My favorite cutbacks enable me to save money while still enjoying the same or close to the same goods or services. These are the “invisible” cutbacks–those that are not noticeable or barely noticeable with a little research and planning.

Some examples:

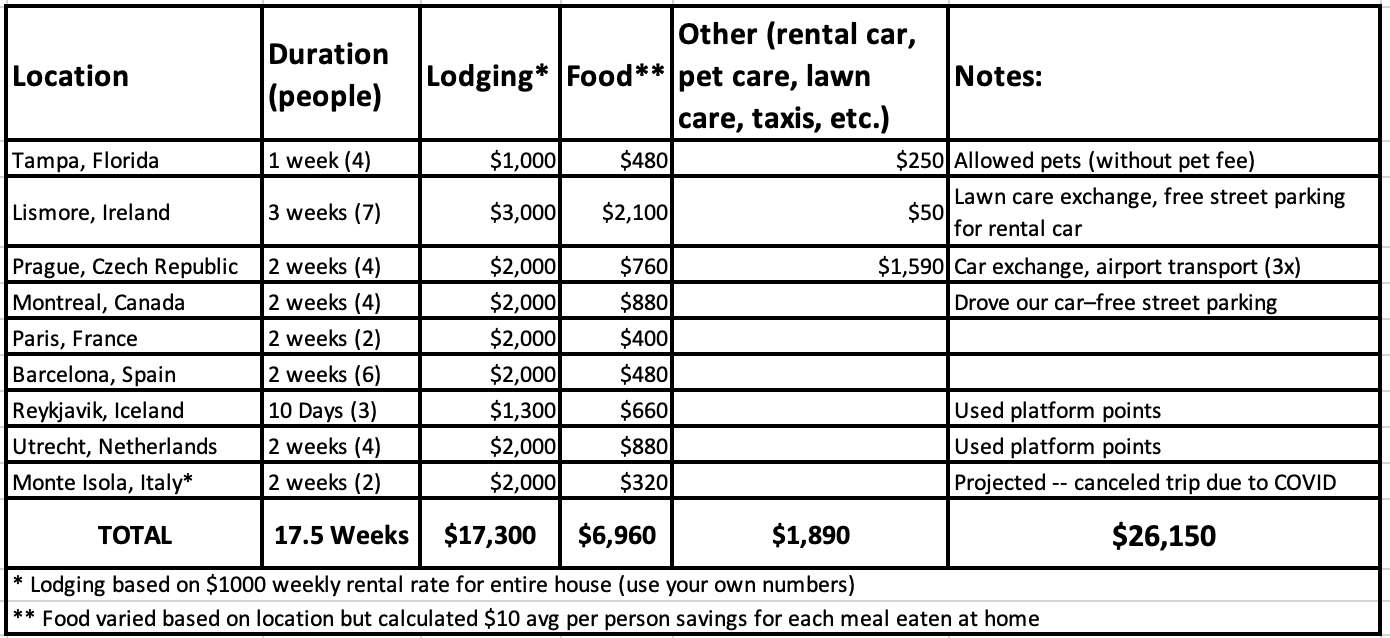

- Taking great trips using home exchanges (free lodging and lower food costs) and travel reward points (super low-cost airfare)

- Going camping with our family instead of paying for high-priced hotels and eating out.

- Arranging free pet-sitters through an online pet sit platform, such as TrustedHousesitters.com, instead of paying for pet care.

- Making high-quality coffee at home and putting it in a reusable travel mug instead of buying disposable cups of expensive coffee on the go (which is also better for the environment).

- Getting free books (physical, digital, and audio) and movies (physical and digital) from the library and not buying or renting them.

- Having my wife cut my hair instead of spending the time and money to go to a barbershop (as a full-time nomad, this is fantastic as I would hate finding a new barber everywhere I go). Note, Pete (aka MMM) has a video on how to cut your own hair.

- Switching to a low-cost cell phone carrier

- Hanging out with friends at one of our houses instead of paying high drink and food prices going out.

- Repair your appliances using YouTube videos and inexpensive parts ordered online AND have a great feeling of accomplishment!

- And a plethora more (useless but funny link to Three Amigos “plethora” scene)

But wait! Many of these suggestions require (1) more of my time or (2) adjusting what I get or do, or (3) both, to save some money. How could I be happier by doing that?

As Dan Ariely and Jeff Kreisler illustrate in their book Dollars and Sense, we humans love getting a bargain (perceived or real). However, instead of being duped into buying over-priced merchandise that is “marked down” (dang marketers using this truism against us) we in the FIRE community find ways to buy the things we need for less and reap the enjoyment of a true bargain.

I have found that spending more either (1) leads to a feeling of disappointment if I feel like I spent to much for something OR (2) has provided only a fleeting amount of enjoyment. (See one of the many good articles on hedonic adaptation.)

It makes me happy to get good value for a lot less money. I can live the same typical middle-class life, but spend way less than most middle-class Americans by making some simple adjustments of what I buy or do.

It makes me happy to repair my refrigerator, microwave, dryer, vacuum cleaner, car side mirror, and lots of other things, saving thousands in repair costs–AND I have increased my skills and confidence along the way.

It makes me happy to save time. If I didn’t repair something myself, I would have to spend time researching a repair company, calling to make an appointment, taking time off to be at home during the appointment, keeping an eye on the repairperson, and paying them a lot for their service (which took me time to earn). I actually save time doing it myself, and I get to do it when I want to, not when the repairperson is available.

KEY POINT: We can do essentially the same stuff AND reap the enjoyment of saving money for our future to buy more time to do what we want!

Main Thing #2: Happiness is primarily derived from family, friends, nature, health, learning, and helping others–not from spending more money.*

*This isn’t just my opinion, check out the extensive research by Dr. Arthur Brooks, Wes Moss, et al. While visiting family and some hobbies may cost some money they can often be done for a lot less (see Main Thing #1)

I have increased my long-term happiness without spending a lot of money.

My best memories with my family involve family game nights (homemade pizzas and hours of playing games), camping and hiking together in the woods, home exchanges to great destinations with travel rewards points paying for most of the airfare, and reading great books from the library out loud together.

My best memories with my friends are from pot-luck parties and hanging out in our backyards around a fire pit enjoying a high quality beverage, or going camping and hiking together. I don’t watch a lot of movies, but when I do, I have a lot more fun watching a video at home free through Kanopy at my public library or renting it online where we can pause and chat about the movie. In contrast I find spending $16 each to go to a movie theater that is so loud I need to wear ear plugs and I can’t chat or take any breaks a lot less fun or interactive.

My wife and I love taking free extended fitness walks along the trails around our quasi-urban house on the edge of DC. We walk along the creek and see deer and birds and lots of other people walking, jogging, and biking. We enjoy the benefits of nature and increase our happiness without spending a penny. As we travel the world, it is a rare location where we can’t find some close-by place for spending time in nature.

Happiness is rarely about the stuff we buy or the amount we spend, but about the time we spend with family, friends, learning, and helping others.

I didn’t need to spend a ton of money going to a restaurant, hotel, or buying books to increase my happiness. I have found that when I spend a lot of money on a meal out or other expensive endeavor, I am often less happy because my expectations were higher and I was underwhelmed.

While we all have felt a jolt of pleasure from buying something new, we need to recognize and separate happiness from these fleeting moments of enjoyment.

Main Thing #3: I am happier when I have less – both stuff and commitments

Separating our identity from our stuff enables us to pursue happiness in less-expensive ways.

As my wife and I sold, gave away, or otherwise disposed of 98% of our personal belongings, I became a different person. Minimalism changed who I am for the better!

By getting rid of my musical instruments, canning equipment, lawn care equipment, cars, house, tools, old files and collections, I released myself from numerous commitments and freed up enormous time and resources.

I jettisoned my lower-priority personas of musician, canner, home owner, etc. to focus on what I truly valued and made me happier and content. Now I’m more aware of the alluring promises of new personas through purchases, and I don’t buy that stuff anymore. I travel, spend more time with family and friends, read, exercise, and learn. I am a different, more content person.

My happiness increased when I bought less.

Conclusion

The FIRE community should not conflate frugality with deprivation or unhappiness. FIRE adherents can live happy and fulfilling lives while also saving a much larger percentage of their income than mainstream Americans.

As modern-day philosopher Naval Ravikant explains, “Money doesn’t buy happiness – it buys freedom.”

The FIRE community needs to proudly claim the key tenets of what makes this movement different from other personal finance philosophies: we are frugal, and we determine and then stick to how much spending is enough. These are the FIRE tenets that Pete and Vicki have long advocated for and they are as applicable today as they were back then.

Spending less does not mean less happiness–done the right way, it can mean more.

COVER IMAGE Credit: “frugality” on keyboard obtained from CreditDebitPro.com