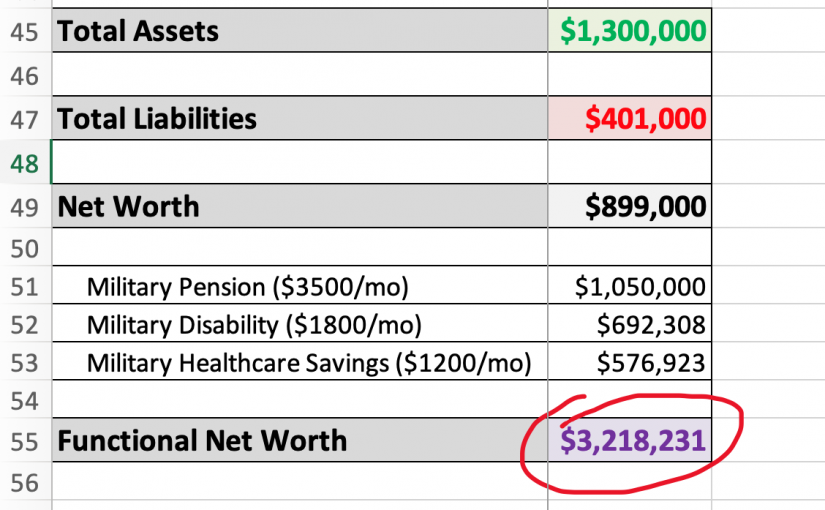

Net worth is a key measure of building wealth. I have been calculating my net worth since 2011 so I can see my progress over time, and it’s a really useful tool.

Many people are familiar with calculating their net worth: you add up the value of all of your assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, real estate, and savings*), subtract your liabilities (mortgage, loans, and credit cards), and the difference is your (hopefully positive) net worth.

Of course, you may have other assets that are harder to account for in this formula. For example, a military pension. My military pension provides valuable monthly income and I believe it should be included in my net worth, but it doesn’t lend itself easily to asset valuation.

How to Calculate the Functional Net Worth

How do we calculate the value of a pension—or other benefit that provides monthly income (or reduces expenses)—and include that in our net worth?

One way is to determine what it would cost to purchase an annuity that provides the same monthly income by pricing an Single Premium Immediate Annuity (SPIA) however, this method doesn’t answer the question of “How does my pension relate to my income from stocks, bonds, and other similar investments?” This is where my handy functional net worth calculation comes in.

To calculate the value of my pension, I use the 4% rule of thumb. This rule, first proposed by William Bengen in 1994 and validated in a 1998 Trinity University Study, is based on historical investment return research.

They found that investments in a combination of stocks (50-70%) and bonds (30-50%) historically returned 4%, annually adjusted for inflation, without running out of money over a 30-year period. If you decide to use a different percentage higher or lower than 4% just divide 100 by your number and get the new multiplier to replace the 25 I use from the 4% rate. For example for a 3.25% withdrawal rate, it would be 100/3.25=30.8.

But Why Calculate the Functional Net Worth?

Before I get into the formulas, I’ll briefly explain why I believe Functional Net Worth is useful.

Many personal finance books, articles, and podcasts in the FI arena make the assumption that most assets are invested in stocks and bonds and real estate. Advice around diversification, spending limits, and other guidance often relates to a percentage of total assets invested.

But if I include additional assets, such as my military pension, I can treat the pension asset as a very stable (i.e., low risk) part of my portfolio. I can invest the cash portion of my portfolio in higher risk investments (e.g., stocks) as a result with less need for investing a large portion in lower-risk bonds.

When I view my entire net worth to include my stable (and inflation adjusted) military pension, the remaining portion of my investment portfolio can take on more risk.

Military Pension

Here is my calculation formula for my military pension:

annual gross pension income*25 or ((monthly gross pension income)*12)*25)

On my Excel spreadsheet the formula looks like this: =((XXXX*12)*25)

where XXXX is my monthly gross pension income

If monthly pension income is $3,500 per month, the calculation would be ((3500*12)*25) and would result in a pension value of $1,050,000 – yep, if you have a military pension paying you $3500 gross per month, you are a millionaire in my book.

This formula takes the annual gross income (before taxes) and multiplies it by 25, or multiplies the monthly gross income by 12 and then by 25.

Social security calculation would work similarly but keep in mind that it can be taxed differently based on your other income which could impact the calculation some.

Tax Exempt Benefits (e.g., VA Disability)

For tax exempt benefits like VA disability payments, the formula is a little bit more complex to account for the tax savings.

annual gross disability income*25 or ((monthly gross pension income)*12)/tax rate)*25)

On my Excel spreadsheet the formula looks like this: =((XXXX*12)/0.YY)*25

where XXXX is my monthly gross tax-exempt payment and YY is the tax rate subtracted from 100 (e.g., for 22% tax bracket the number would be 0.78, for 12% it would be 0.88).

If your monthly disability payment is $2000 per month in a 12% tax bracket, then the calculation would be =((2000*12)/0.88)*25 and would result in a disability value of $681,818. This number would be higher if you are in a higher tax bracket.

Military Healthcare Benefits

This same formula (minus the low annual TRICARE premium, if applicable) also works for calculating the net worth value of the military retiree lifetime healthcare benefits. To estimate this value, I estimate what I would pay for commercial healthcare, either through an employer or the state exchanges (adjusting for any subsidies I may qualify for).

With my military income, rental property income, and retirement account income, I wouldn’t qualify for much (if any) subsidy. For a $1500 unsubsidized monthly healthcare premium (using a 22% tax bracket), the functional net worth value would be ~$576,900.

Conclusion

Calculating functional net worth, not just net worth, is a very useful exercise for military retirees and others with pensions or disability payments.

By adding the projected value of pension income and other high-valued benefits into my net worth, I am able to better identify what portion of my FIRE number needs to be investments, and how those investments should be diversified.

I can also better manage the risks of my investments over time. Seeing the equivalent investment amount, I would need to provide similar inflation-based income, as my pension and health care benefits, is a valuable marker of the progress I have made toward achieving FIRE.

* I don’t include cars, furniture, clothing, or other household items in my net worth calculation, because I view them as depreciable expenses that will sell for much less than I purchased them for and will generally need to be replaced when sold.