“I hate cleaning!”

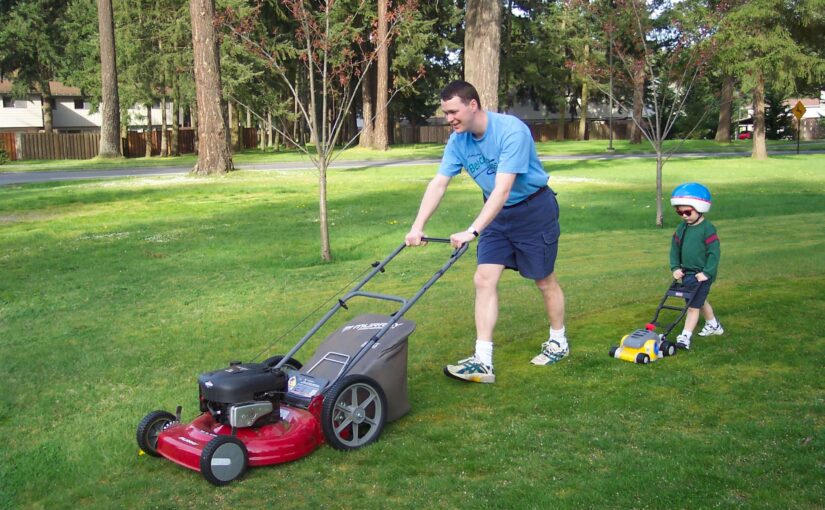

“I wish I didn’t have to spend my precious time off mowing the lawn.”

These are common refrains to justify spending money to outsource our daily chores in an effort to protect a few hours of down time. But can we truly buy back our time? And if so, is it worth it? If we’re pursuing financial independence (FI), what does this kind of time buy-back mean for our FI number and the time until we reach FI? I’ve asked myself this question a lot over the years. In the past, I’ve hired a twice a month housekeeper, and I’ve hired both kids and professionals at various times to mow my lawn in an effort to free myself from these routine chores. Let’s take a closer look at how much time I actually bought back.

Higher Expenses Now Will Delay Achieving Financial Independence

This article is primarily for those who have not achieved full FI (i.e., you have the financial ability to retire early—to have complete time flexibility). If you have already achieved full FI, then only my discussion on opportunity costs and time efficiency apply.

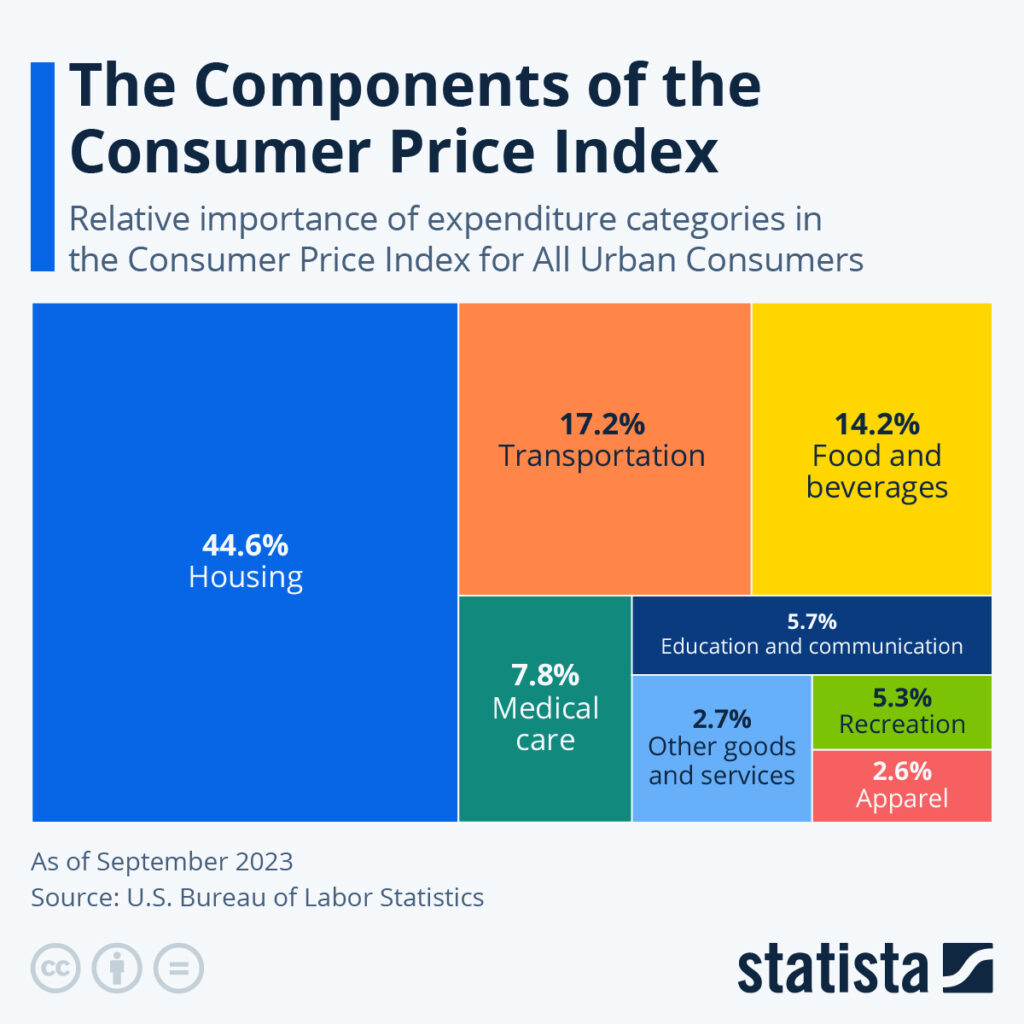

The formula to achieve full FI is pretty straightforward—you need enough passive income from investments, real estate, or pension to cover your expenses. In simplest terms: the higher my expenses, the longer it will take me to achieve FI, especially if I plan to keep the expense of a housekeeper or lawn care after achieving FI.

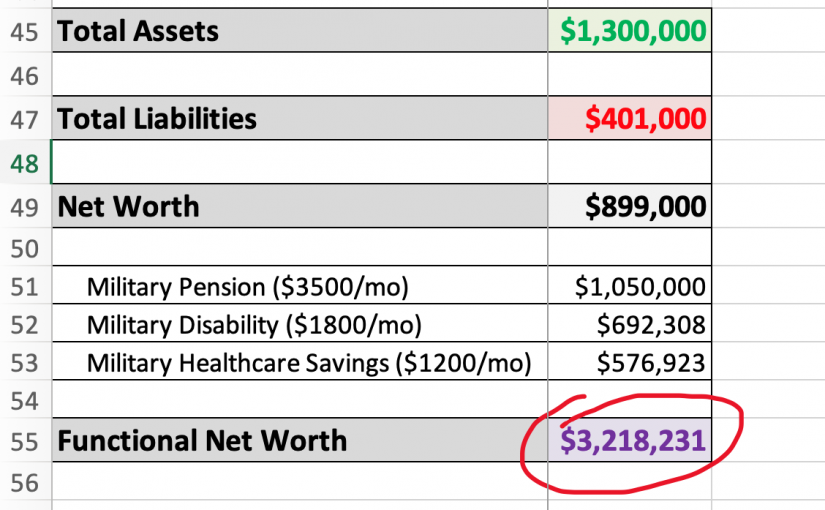

Using the commonly accepted 4% rule of thumb, we need 25 times our expenses in investments to achieve FI (this is called our FI number). Roughly speaking, adding a $100 a month expense will require an additional $30K to our FI number. If I hired a housekeeper to clean my house every two weeks for $120 (inexpensive for the DC area), then I would prevent $260 average per month of after-tax money from being invested and compounding toward my FI number.

That would add $78K to my FI number! At a 100K gross salary, subtracting Federal and state income tax plus Social Security and Medicare taxes, I would need to work an additional year to save that amount of after-tax money. That will include more time spent getting ready for work and commuting that year, making my per hour wage even less.

Buying back small increments of time now will require me to pay it back later by having to work more hours. You might be thinking “But I make $48 per hour, and the lawn guy only charges me $30 an hour, so I will gain back time.” Maybe. Let’s take a closer look at what our time is actually worth.

How much is my time worth?

Before deciding if it is worth trying to buy back our time, we need to first understand how much our time is worth, so we have a number to compare with the cost of hiring someone. That will help clarify if it’s worth the extra time we would need to work to pay for hiring out our chores. It is not as simple as looking at our gross hourly wage.

If our salary is $100,000 per year (gross), then a simple division of 52 weeks in the year and 40 hours per week gets me to the figure of $48 per hour. This is a gross number and doesn’t include the reductions for income tax (federal and state) or social security and Medicare taxes.

Let’s say we are in the 22% marginal federal income tax bracket (my spouse works also). Add to that the 6.2% combined social security and Medicare tax (entrepreneurs also pay the employer amount), and 5% state income tax (this will vary by state), then our actual net pay after taxes for each hour is about $32 per hour net. That is one-third less than that $48 gross! And a whole lot closer to what the lawn guy is charging.

But wait…this doesn’t account for the other costs of work—time and transportation costs getting to work, expected donations to coworker birthdays, showers and socials, potential higher costs for work clothes and eating lunch at work, etc. Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez provide a good method for understanding the true cost of working in their excellent book Your Money or Your Life. Often, we overestimate how much we truly earn from work and underestimate the true cost of our expenses.

The $260 monthly cleaning fee would require that I work at least an additional 8.1 hours each month to cover the cost ($260 divided by $32). Can I clean my house each month faster than 8.1 hours? Yes, I can! And by doing so, I can let that $260 per month compound in my investments and help me buy my complete time freedom much earlier. If I earned twice as much per hour or more, then it would take many fewer hours of working to cover the costs.

Many of us work a set 40-hour week without the choice to work overtime, so we couldn’t decide to work an extra 8.1 hours each month at our regular job. Instead, we would need to defer our retirement date by approximately a year (again, assuming we made $100K gross annually), or work a side-hustle. Most side-hustles earn less than our regular job, so we would actually be losing time each month trying to pay someone to do the cleaning or lawn mowing work for us—not a great bargain!

How much time does it take us to do the chore we want to outsource?

To make an accurate financial decision, we need to have a realistic estimate of the average time it takes to do the same work (e.g., the cleaning a housekeeper would do, or mowing and edging the lawn). For housecleaning, we need to dust, vacuum carpets, sweep hardwood floors, scrub two bathrooms and kitchen, and change and wash the sheets. All of which would take me three hours (your time may vary). Mowing the lawn requires gassing up the mower, pushing it around the yard, and pulling out the electric trimmer to complete the edging. All of which takes me about 45 minutes each week during the spring and fall seasons. But it isn’t as simple as comparing the cost with just the time it requires to do the chore itself. We need to include the time it takes us to manage the hired contractor.

How much does it really cost to hire someone?

In addition to the time needed to earn the money to pay for these added expenses, it also takes time to schedule the service, straighten the house so the cleaner can vacuum or make the beds etc., write the check (or get the cash), provide the mower, cleaning supplies, or other items, and fix/address any subpar work. All this adds up. Is it worth it?

Am I truly getting back the time it would take me to do it?

To find out how much time we are actually saving, we take the amount of time it takes us to do the chore and subtract:

- Any additional time we need to work at our job to pay for it using our net pay minus any costs of working.

- The average amount of time needed to hire and manage someone (scheduling, quality control, payment, etc.)

- The portion of time we could use to multitask during the chore. (I listen to audio books and podcasts, so doing the dishes, cleaning the bathroom, or doing laundry doesn’t take away from my time since I’m multitasking while listening).

So, assuming the financial calculations work and you can spend less time working at your job to hire the house cleaner or lawn care company, are you truly getting back quality time?

As I mentioned earlier, this is fundamentally a decision about extending your working time to afford these higher expenses. Will the extra 40 minutes a week “saved” mowing the lawn be spent doing something you enjoy more than the complete freedom we have after achieving financial independence and no longer need to work?

Will the cleaning or mowing service occur during your prime weekend or evening time (since that may be when the kid can mow your lawn or the cleaners can clean your house). Will you have to leave while they are working? If you remain at the house, you still have to deal with vacuum cleaner or lawn mower noise that may impact the quality of the time saved. This becomes even more difficult if you work from home and have less flexibility in scheduling these noisy chores.

Opportunity Cost: not all time off is created equal

Consider the opportunity cost of investing the money instead, retiring earlier and having extra time that is fully usable. Getting an extra hour or two a week won’t enable more travel in your life, achieving other bucket list items, or following where your interests lead, but getting to FI earlier will.

Once I achieved FI and retired early, every possibility for my time became open to me. I was able to get rid of my possessions and travel the world full-time. I not only don’t have to mow my lawn or clean my house, but also I no longer have to schedule anyone else to do it for me, or quality check their work, or avoid the house while they are there.

An hour when I have achieved full FI (combined with the rest of my hours) is more flexible, and I argue more valuable, than a random hour dispersed throughout a work week that is difficult to capture and combine with other free time. So often that purchased time gets lost in our hectic schedule and quickly filled by our endless list of other tasks.

What about the Intangibles?

I get it that some chores are just not enjoyable, even if we also listen to a book or podcast while we do them. So, for those few chores that we truly dislike (cleaning a bathtub and shower curtain is in that category for me), then it may be worth spending some retirement capital on that chore now, even if it delays our actual FI date by a little—but we should make that choice with eyes wide open.

In contrast, many chores are satisfying. I find lawn care and gardening to be meditative and something that gives me great satisfaction when I am done. The yard always looks (and smells) nice after mowing and trimming and I feel great getting the exercise. My beer afterwards always tastes better than if I’d hired out the work.

What about the quality of work? Hiring someone does not necessarily mean that the work being done will be high quality. I have found that most kids in the neighborhood hired to mow and trim usually do an OK job, but in most cases not to the level that I would do myself (e.g., blow and/or pick-up the grass clippings from the sidewalks and driveway, avoid grass clumps, mowing on a day that the grass is dry, etc.).

Similarly, I have found house cleaners do not understand how I like to clean the kitchen. For example, I scrape the dishes and load them well-spaced in the dishwasher so they clean better and I don’t put wood items (knives and cutting boards) or Teflon cookware in the dishwasher. I was often redoing their work in the kitchen.

So Can You Buy Back Your Time?

In a nutshell, not really, unless you are a very high-income earner making multiples above the $100K salary range. For us average salary earners (US median household income is ~$81K per year), it is fundamentally a trade (possibly a loss) of our future time freedom for small bits of time now. For me, when I was still in my house, I let the housekeeper go after a couple years trial (becoming a minimalist helped reduce my cleaning!) and I chose to mow my own lawn.

Whether the financial calculations work or don’t work for you, there may be other factors that impact your decision to hire out the work. In the end it is a personal choice—run the true numbers, analyze the quality of time “purchased,” and compare it with opportunity costs now and in the future.