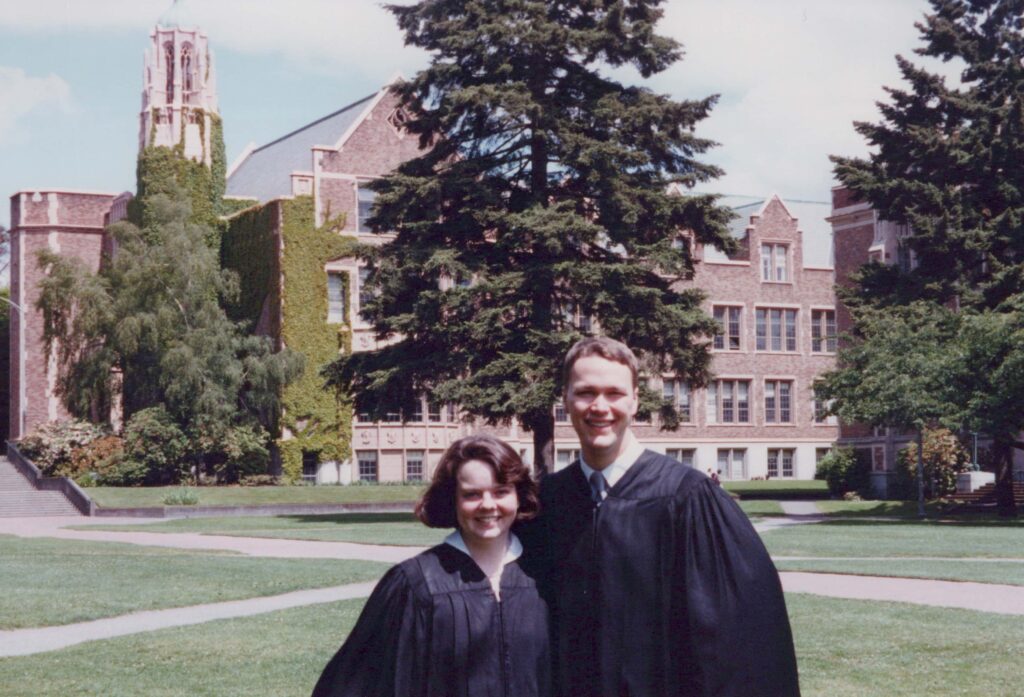

My dad was a “jack of all trades,” and there was little he couldn’t do himself. He made his own soap, handmade moccasins from a bear hide he tanned himself, reupholstered furniture, built a barn, a double-axle trailer (did all his own welding), laid bricks, rebuilt a carburetor, kept bees, added a bedroom and bath to our house (and did all his own plumbing and electrical), installed a wood-burning stove, and then built an entirely new house for his retirement years. During the high unemployment of the early 80s, my dad was laid off from the logging industry in our depressed rural county for over a year and a half, but he was able to do piecemeal handyman work, sell firewood, keep a garden, and hunt to keep food on our table until he was able to find steady employment again.

[Cover Photo Caption: Building a fence at one of our rental houses. Our landlord was so impressed he paid me $500 for the fence when we moved out!]

I was his (often involuntary) helper. I remember holding a light very still for what seemed like hours (but was probably only 20 minutes) in the freezing cold under the car at night while he repaired it. And though I was sometimes reluctant in these adventures, I absorbed a lot. His example taught me about self sufficiency and the importance of having a broad base of skills.

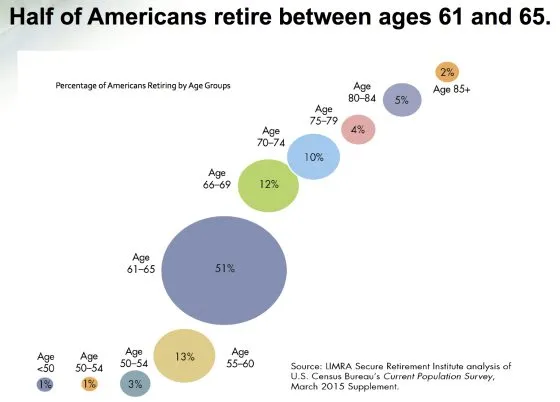

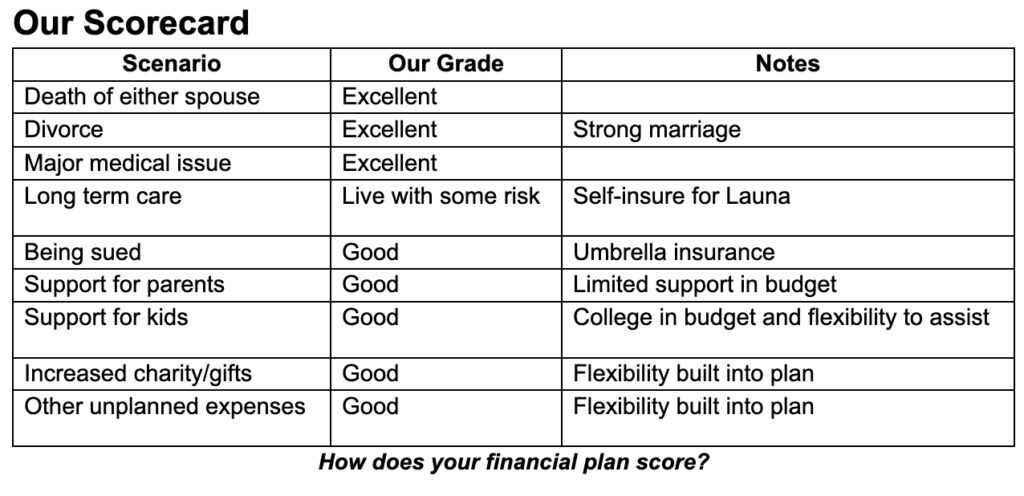

Skills are assets. While they don’t show up on our net worth tracking spreadsheets (maybe they should?), they represent future value to us in terms of cost avoidance, self reliance, and accomplishment. Each time we learn a new skill and use it, we increase our net worth. So often we blindly just pay other people to do things for us that we could do ourselves and increase our skill-based assets. Here are six reasons for doing things ourselves instead of hiring out the job.

Reason 1: Skills save money (cost avoidance).

When we think about do-it-yourself (DIY), we often think about saving money. DIY is spending some of our time doing or making something instead of paying someone else a lot more to do it or make it for us. For example, when Launa and I bought our house in Virginia, we needed a shed for our bikes, lawnmower, and other tools. Instead of paying $6,000 for a new shed delivered to our house, my father-in-law (Pop) and I built one ourselves. For less than $800 in materials, I had a 8’x12’ shed (inside dimensions) with windows, a double-wide door, and attic space. If I counted the $1300 in net salary lost for the hours I spent building it (which I don’t, as I’ll explain later), I still saved almost $4,000!

My wife and I DIY our trip planning and we save a lot of money doing so. For example, when we hiked inn-to-inn along Hadrian’s Wall in England, we paid $1600 (56%) less than we would have if we booked the same trip through a popular tour operator. That’s good pay for about two days of work! But we also got a trip tailored to our exact preferences, we stayed closer to the wall some nights than the tour would have arranged, AND we gained a deep knowledge of the trail which enhanced our hike. We enjoyed similar savings by planning our trips along the Via Degli Dei in Italy, the Lycian Way in Türkiye, and the Archipelago Trail in Finland.

But DIY isn’t just about saving money. It provides numerous other benefits even in cases where it costs a little more than paying to have it done by someone else.

Reason 2: New skills keep us learning.

Life-long learning has a positive impact on our mental health and well being. Instead of spending our free time on passive activities like binging TV series, we can engage in activities that teach us new skills. DIY, baby!

DIY is project-based learning. Building that shed with Pop taught me a lot about construction. I learned how to frame out the walls, design the barn-style roof, install windows and doors, and shingle the roof. Little of that I knew how to do before we started, but we figured it out.

Over the years I have learned basic electrical and plumbing work, drywall repair, computer programming, property management, personal finance, gardening, canning, and appliance repair to name just a few. The learning and problem solving inherent in DIY projects is great for my brain and provides an outlet for my creativity.

Building a tree house with Pop. This was a fun project to design and build together.

Reason 3: Learning skills instills self reliance.

While saving money is great, skills provide flexibility and value in a changing world. This idea was well expressed by Jacob Lund Fisker in his book Early Retirement Extreme, where a primary goal of his was to break free of the work-buy-work cycle and learn to do things himself. By having a multitude of skills, we can weather unpredictable changes in employment (like my Dad did), our health, prices, and the supply chain.

By being more self reliant, I don’t have to pay higher prices. I can skip a long wait for a car repair appointment or for a contractor to fit me in. I can get things done on my own timeline.

Reason 4: Skills save time (usually).

It might sound counterintuitive, but many times doing something yourself can save time over hiring someone else to do it. For example, when the side mirror on our car was broken off by a passing car, I could have called around for quotes, scheduled an appointment, drove the car across town to the shop and then either waited a few hours for the repair work to be completed or had my spouse pick me up and bring me back, THEN paid for the repair, drove home, AND worked 12.5 additional hours to pay the cost difference from doing the repair myself.

Instead, this is what I did: I quickly searched online for aftermarket parts, ordered the mirror to fit my car, reviewed the repair tutorial video provided by the parts website, bought the $11 door-cover-remover tool at the nearby auto parts store, and followed the video tutorial to replace the mirror and test it. It worked great! In a total of 2.5 hours I did myself what paying someone else would have taken 15 hours or more of my time. Even if, for example, my salary was twice the national average, it would still take 9 hours to pay for it! So while it might seem like paying someone else to do something for us will save time, it often takes more time than doing it ourselves—what I call “the tyranny of convenience.”

Not to mention, I was really proud of being able to do it myself which leads me to…

Reason 5: Skills reward us.

Repairing my refrigerator, building a shed, replacing a bathroom sink, and patching drywall is extremely rewarding. I enjoy the process of learning how to do something and then exercising those skills and seeing the tangible results. Every time I complete a DIY project I have a great sense of accomplishment and take pride in knowing that I was able to figure it out myself. As I write this post, just thinking back over the many projects I have completed fills me with joy. I don’t feel that joy when I pay someone else a lot of money to do the work for me.

DIY renovation of narrow kitchen pocket door into an archway before (left) and after (right). We enjoyed our kitchen and living room space far more with this change (and I suspect made our house more valuable).

Reason 6: Skills build self confidence.

On top of a sense of accomplishment and enjoyment I get from DIY projects, I also garner more self confidence. The more I am able to do myself, the more confident I am that I can tackle more complex projects. I didn’t start with building a shed. I started with hanging pictures and replacing furnace filters. Then I progressed to replacing door knobs and repairing lamps switches which progressed into minor drywall, electrical, and plumbing work. The more skills I learned, the more confident I became to tackle increasingly complex projects.

How can you build your DIY skill set?

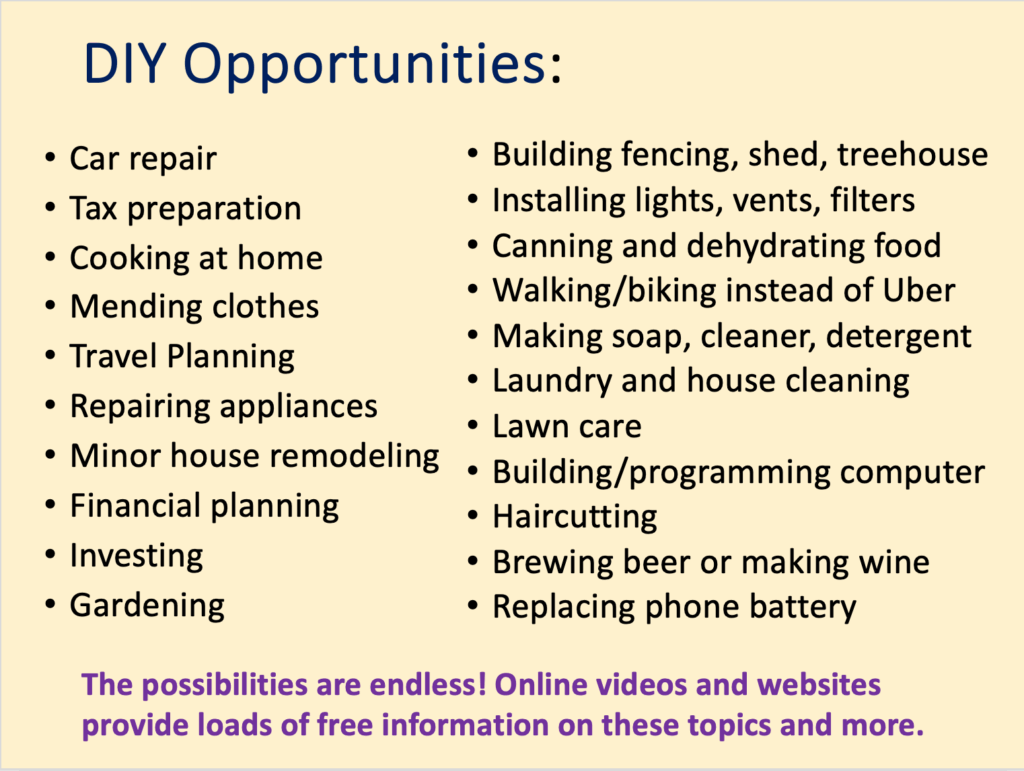

DIY isn’t just house repairs or fixing your own car. It is doing anything that we might hire someone else to do for us to include taxes, investing, moving, travel planning, rental property management, gardening, yard maintenance, making coffee, and cooking. It can also be more abstract skills like walking or biking instead of taking an Uber, learning to exercise and eat well, or doing a home exchange instead of purchasing lodging on vacation. Here is a list of some DIY opportunities to help you brainstorm:

What skills do you already have that you could expand on? What would you like to learn how to do? Identify easy opportunities that could be quick wins to build your confidence. Maybe start with mending a hole in your favorite shirt, sewing on a button, replacing your windshield wipers, or making pizzas at home (I love my wife’s homemade pizzas!). Don’t start with something too big like replacing the brake pads on your car, as you risk being overwhelmed and losing confidence.

Tap into available resources. Search online—there is a video, website, or interest group for every type of DIY project. The wealth of online help hasn’t failed me yet!Seek out a mentor. Local groups, friends, neighbors, and relatives can be great resources. I learned a lot from my Dad, my father-in-law (Pop), and friends on how to tackle different projects. If you want to brew your own beer, I suspect someone you know can help you get started.

Some tools you’ll need can be borrowed from your library or neighbor, and many tools can be rented, too. But even if you need to buy a tool, just one DIY project will normally cover the expense, and subsequent uses make it even more cost effective. Over the past 35 years I had built up a set of tools that I frequently used to complete my DIY projects, from basics like a hammer, multipurpose screwdriver, and drill to specialty items like canning equipment, a mitre saw, and a haircutting set (my wife has cut my hair since 2006).

Take pride and celebrate your DIY wins—and that includes when a project doesn’t go to plan. You are learning new things and building a skill set, even if you need a second (or third) try, or a little help this time to get it done. My wife and I are each other’s biggest fans and support and appreciate our DIY skills. Take photos before and after and share them online and with friends, co-workers, and family. The positive feedback is energizing!

Even after I downsized and no longer have a house, car, or many belongings, I still exercise my DIY skills. I help family and friends with projects at their houses or with financial planning. I sharpen knives at our long-stay accommodations and even do some minor repairs (I even built a bed frame for one host!).

DIY projects feel great, save money and time, help us learn things, be more self reliant and self confident, and help others.

How are you increasing your skill-based assets?

I built this frame for a long-stay AirBnB which took me about 3 hours (with the host’s approval and reimbursement for materials cost). It kept the mattress from sinking into the well of the bed frame (clearly not the right mattress for this frame). I slept much better afterwards!