Five years ago, I took the leap to retire early—fifteen years before Social Security’s full-retirement age. I left my career as a civil servant at the Department of Defense at its peak—not just in terms of my highest compensation but also my greatest influence and status. And yet, it was one of the best decisions I have ever made. Since retiring early, my life has changed for the better—no regrets. Looking back on these past five years, here are eight things I learned about early retirement and myself:

[Post Photo Caption: Immersing myself in history at the Giza complex in Egypt as a full-time traveler]

Lesson 1: You don’t have to have your retirement figured out before you retire.

You really don’t. I wrote about this in my post on myths of early retirement, but it deserves some additional explanation as I received some feedback. When I retired, I had a general idea that I wanted to follow my curiosities and no longer spend the majority of my waking time and my physical and mental energy earning more money than I needed. When I left my full-time job, I had no idea that I would become a minimalist, find my dream job, quit that job, and travel the world full-time for two years and counting. I didn’t know how I or my retirement would evolve before I retired, and I didn’t need to know, yet. That knowledge unfolded.

When you or I retire, we don’t mysteriously become another person. Our minds don’t turn to mush and we are only saved by careful retirement preparation, planning, and practice. Instead, we wake up the next morning like we would on a long weekend or vacation (hopefully without an alarm) refreshed and ready to tackle the next chapter of our lives to include figuring out what that chapter will look like. I didn’t suddenly stop being a doer and lose any sense of my ability to learn things and get things done. Quite the opposite. I now had ample time and a full tank of physical and mental energy that until now I’d been applying toward work to apply toward figuring out retirement.

Before retirement, when I was physically and mentally exhausted working long hours at my job and fitting in my everyday life chores around that, was not the right time to try out new hobbies or make new retirement friends. Forcing a new hobby into my already busy life and precious little down time, particularly one that would benefit from daytime hours and my full energy, would have added to my stress and risk me resenting the new endeavor that I might otherwise enjoy.

It is OK to not know what you want to do in retirement. Leaving work frees up the time and energy to explore and try out new things and meet new people. I learned an enormous amount about myself after retirement because I had the time, energy, and resources to do so. We don’t have to have it all figured out in advance—we can leverage our time in retirement to do just that. Protect what little white space you have in your working life and know that retirement will provide ample time to decide what to do next.

Lesson 2: Stress testing your retirement plan works.

Stress testing my wife’s and my retirement plan has paid big dividends in how well we are enjoying our retirement. It made us both comfortable to retire early and brought comfort and confidence as our plans in retirement have evolved significantly over the last 5 years.

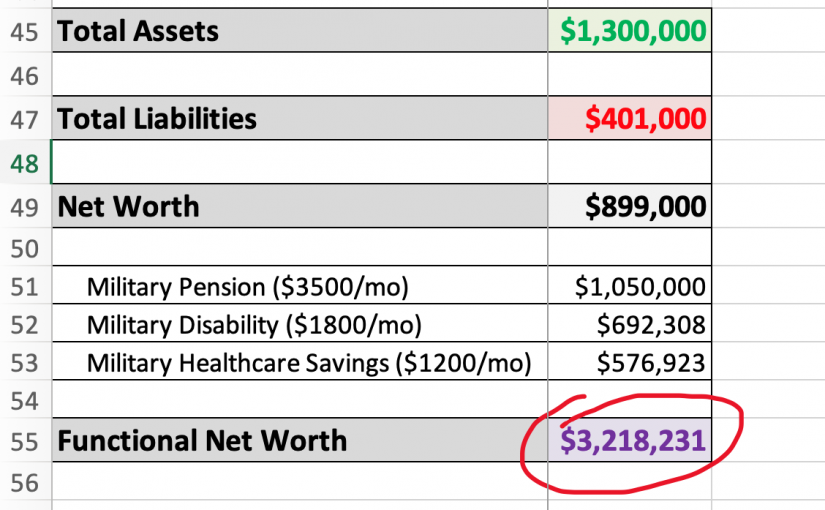

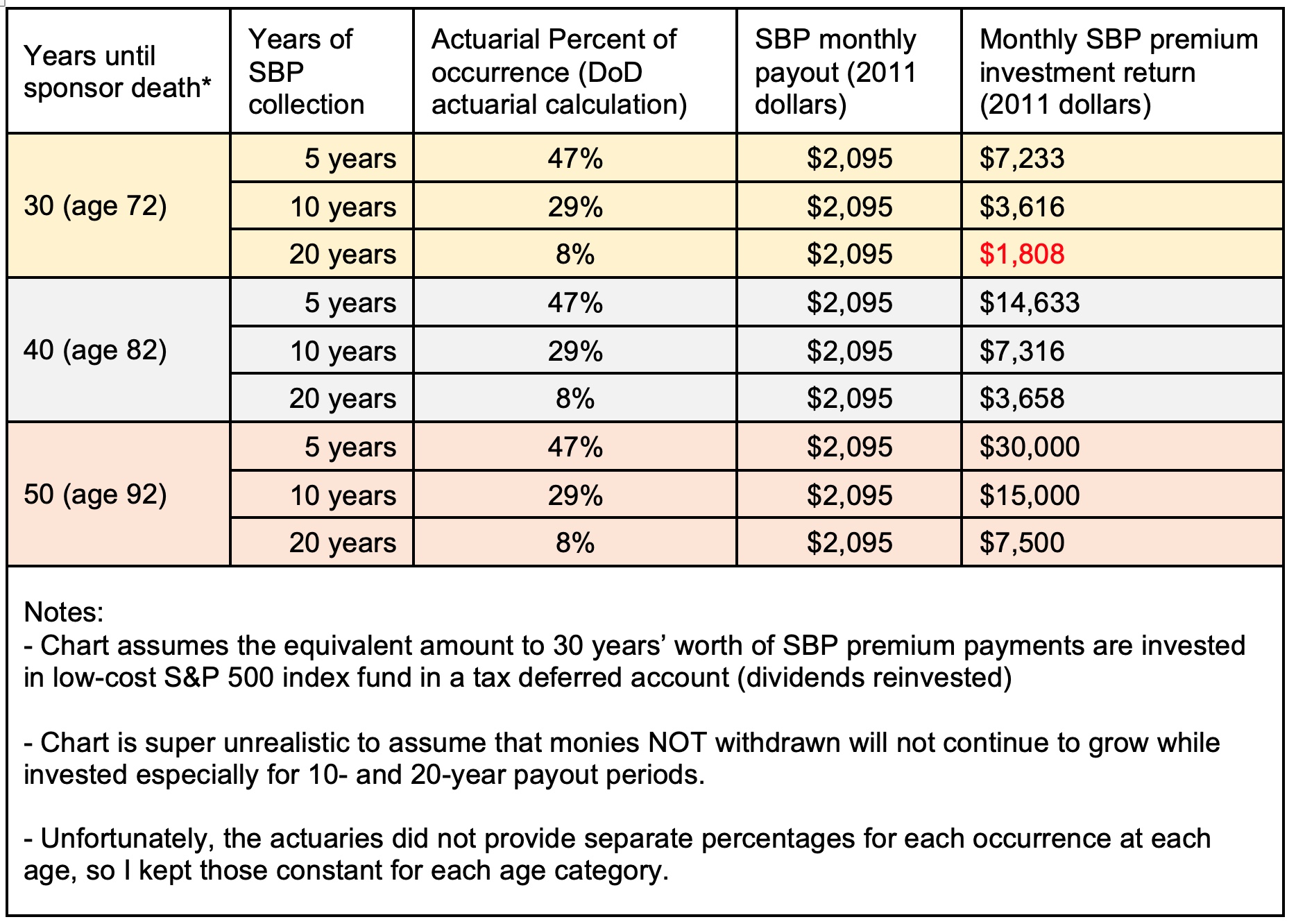

Stress testing isn’t just calculating our safe withdrawal rate that our investments would provide and comparing that to our known expenses. I also stress tested our retirement plan against unforeseen life changes that might derail our plan, such as one of us dying early, divorce, long-term care needs, or major health challenges. We also tested our plan against increased spending on family and favorite charities beyond our planned retirement spending levels.

Due to this stress testing, handling a surprise major health diagnosis a year into retirement didn’t derail our plans. Similarly, increasing our financial support of our family and donating more to causes we value hasn’t altered our plan. Stress testing our plan helped ensure our successful retirement. I provide more details on stress testing my retirement plan here.

Lesson 3: Trusting your retirement plan is key to enjoying retirement.

There is an important mental component to overcome when retiring early—fear. Fear that inflation will skyrocket, fear that the stock market will tank for an extended period, and fear that we missed planning for some unknown expense that will derail our retirement. I learned that this fear is unfounded. The 4% safe withdrawal rate that underpins financial independence is already very conservative and includes historical fluctuations in inflation. All of my double checking of spreadsheet formulas, running performance scenarios, and stress testing our plan made our plan even more solid. I had to remind myself that we have a lot of flexibility to adjust spending which creates options in our plan. My fear was self-imposed and unfounded, and by recognizing it, letting it go, and trusting my plan, I greatly increased my contentment with my choice to retire early.

Lesson 4: Work identity is a self-imposed weight.

Our identity is frequently intertwined with our jobs. In the US, asking what you do for a living is a common first question when meeting someone new. As a society, we put a lot of weight on our work and measure our importance by our titles. I was no different. I was proud to tell people I was an Air Force officer for 20 years, then a civilian director at the Pentagon after that.

So when I decided to retire early, I was worried about what I would tell people when they asked what I was going to do after leaving my job. A significant reason I decided to become a graduate student after retiring was to be able to tell people at my old job that I was going back to school full time, as they (and I) struggled to understand my decision to leave my hard-won director’s position. I thought “grad studies” carried a level of respect and fit within society’s paradigm of what I should be doing with my time. Telling people I was “retired” sounded less important and I assumed people would think less of me. But the truth is, all of the weight and importance of a work identity was self-imposed. When I let that go, I was better able to discover who I really was—what was most important to me.

When I left graduate school, I decided to own my early retirement and just tell people that I was retired. I discovered that people didn’t care (many were intrigued) and the importance of the title was really about my own judgment of myself.

Our identities should not be primarily defined by our jobs. My identity consists of many things. I am a husband, father, brother, son, and friend. I am a traveler, reader, hiker, minimalist, language learner, coach, student of history and of life, and writer. Who I am has changed over time and I will continue to evolve. By recognizing the power and weight we give to our job identity, we can put it into perspective with all of our other identities and help us mentally transition to early retirement more smoothly. The self-imposed weight of paid work titles no longer overshadows who I really am—a proud early retiree.

Lesson 5: Even with total time freedom, you have to focus on your top values.

Since retiring I have learned to focus on what I value most. I knew beforehand I needed to focus more on my health, so that one was easier. But it took more effort to identify what I wanted to do most with my newfound time freedom. I tried graduate school to pursue my love of history, cycling, gardening, and working my dream job educating service members on personal finance. I also wanted to travel more (a lot more) and spend more quality time with my family and friends. I wanted to improve my language skills, and read more. Trying to do all of these and keep up our house, cars, yard, and other commitments meant not doing any of them very well. I found that by slicing up my time with so many activities often derailed what was most important to me.

A big step in helping me refine what I valued most was minimalism. I began a two-and-a-half-year process of letting go of everything that was holding me back. Through that, I was able to identify my top five values and actively stop doing numbers 6 through 20 that were eating up my time and energy. I discovered that the more I traveled, the more I wanted to travel. I also didn’t want to repeat my mistake of not spending enough quality time with my dad before his Alzheimer’s worsened. As I shed my possessions my clarity of what I wanted to do came into focus—lots of slow travel, more quality time with family and friends, focus on my health, reading more, and improving my language skills and history knowledge.

By letting go of my full-time job and the physical possessions around my lower value interests, I was able to focus on what was most important to me. I know my values will change over time, but the process I learned, of identifying what I value most, will remain.

Lesson 6: It’s harder to transition to retirement if your partner still works.

Having time freedom as an early retiree was (is!) fantastic, but early on I didn’t have complete time flexibility as Launa (my wife and best friend) continued to work for two more years. Similarly, my other friends were working also. So, while I enjoyed riding my bike along empty trails, hiking when no one was around, visiting DC’s fabulous free museums mid-week, I didn’t get to share these experiences with my best friend and compound our memory dividends.

To mitigate this challenge, I pursued projects that helped fill my days and free up time when my wife and other friends were free. A key thing was doing shared chores like grocery shopping, laundry, dishes, car maintenance, and other errands during the day so when Launa was off work we could fully enjoy our evenings and weekends together. I spent my first year of retirement as a full-time graduate student. I completed most of my reading and writing during the day. I pivoted from grad school to personal finance coaching during my second year and worked in my dream job. But when my wife decided to retire early also, I was very motivated to align with her six months later when I quit my dream job.

For the last 2.5 years, retirement has been spectacular because we are enjoying it together with complete time freedom. While I certainly enjoyed my first 2.5 years of retirement, I was still tethered to the working world’s schedule. I learned that the benefits of early retirement can be more fully realized when your timing aligns with your partner.

Lesson 7: Having complete time freedom is gold.

Not all time is equal. I recall when my work day was chopped into a hundred 5-minute periods responding to email, voicemails, and putting out the latest fires with leadership and my staff. Though I frequently worked long hours, I struggled to find time to tackle the most important tasks because they required hours of uninterrupted time to accomplish. I had the same amount of time each day, but it wasn’t effective time when it was chopped into small pieces and limited my options for what I was able to accomplish.

Time in daily life is similar. Four hours of free time broken into 15-minute chunks across several evenings after a long day of work is less useful than a four-hour block of uninterrupted time when I am well rested and focused. Trying to buy back our time in small increments, like hiring housekeeping or lawn care, rarely provides us valuable time to spend. Applying this to different financial independence paths (below), we can see different levels of time value.

Coast FIRE: Having enough invested early in life to be able to retire in your 60s (aka coast FIRE) is better than the traditional retirement path (slowly investing 10-15 percent every year until age 67) as coast FIRE offers more flexibility of work choices to include part-time opportunities. But you will still have to work to pay the bills until retirement, so your time is not fully your own.

Barista FIRE: Having your passive income cover some of your expenses and having to work part-time to cover the rest, such as working as a barista (aka barista FIRE) also provides more flexibility than the traditional retirement path, but work still controls a portion of your schedule and limits your time options.

Sabbaticals: Taking periodic sabbaticals, either within a job or between jobs, can provide some increased time flexibility, but it is limited by the length of the sabbatical and your financial situation. For example, you cannot commit to a 2-year volunteer opportunity if you only have 3 months off. Work sabbaticals often delay achieving full financial independence by spending early savings before it can compound.

Being fully financially independent with the ability to retire early (aka traditional FIRE) provides the most time flexibility. Every hour—every day—of retirement has every possibility. You decide (not your boss) what to do with your time. It wasn’t until both my wife and I achieved full financial independence that I realized how free my time was. We can now say yes to anything and our only time limitations are those we impose on ourselves—pure gold! Knowing how much more valuable my time is now, I wouldn’t do it any other way.

Lesson 8: My previous accomplishments reduced pressure to pursue big external goals in retirement.

I recognize that the earlier one retires the harder it might be to not continue working for pay to fulfill the human need for accomplishment. I worked 30 years full-time after college. Twenty years on active duty and ten years as a civil servant at the Pentagon. My jobs focused on service to military members and their families. I am proud of all I accomplished in the working world. Also during those 30 years, I served on the board of directors for two nonprofits, served as president of the neighborhood civic association, and coached recreational soccer for 25 seasons.

I share this because I no longer feel that strong desire to “make my mark” externally as I did when I was younger. I don’t need to “find my purpose” in early retirement. My need for purpose was fulfilled with accomplishment over those 30 years. I had long strived for external validation (promotions, awards, accolades, prestige) that my jobs readily provided. Looking back, I can see that one downside of this external focus is that I had prioritized it over taking good care of my health and spending more quality time with my family.

Now as an older early retiree (I retired at age 52), I feel freer to focus on myself and my family and friends. This was something I knew was missing, but I wasn’t able to take action until after I freed myself from the inertia and gravitational pull of the working world. I have learned to focus on what I value the most, no longer trying (and often failing) to squeeze in health and family around work commitments.

My first 5 years of early retirement have been great. I trusted my plan. I shed many societal pressures related to identity and accomplishment. I learned the value of time freedom and having someone to share it with. I learned about the power of minimalism in helping me focus on what I valued most. I let myself change and I look forward to continued evolution in the next five years of early retirement.