I used to be a cyclist, gardener, canner, aspiring musician, soccer coach, coin collector, stamp collector, home owner, DIY handyman, and Department of Defense hospitality expert.

I am no longer those things. I found that by selling, giving away, or otherwise disposing of my guitars, soccer gear, biking gear, coin and stamp collections, work files, house, and many, many, other possessions related to these pursuits, I was freed from the personas that took away my time and focus from the things that I wanted to be and do the most.

In his time management book Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkman challenges us to focus on our top priorities. He shares a story attributed to Warren Buffet, in which the billionaire advises us to make a list of our top 25 priorities, then focus on the top 5 only, actively avoiding the remaining 20 items. Those items prevent us from spending the time needed to do our highest priorities very well.

Burkman himself is not this prescriptive. He explains, “You needn’t embrace the specific practice of listing out your goals (I don’t, personally) to appreciate the underlying point, which is that in a world of too many big rocks, it’s the moderately appealing ones—the fairly interesting job opportunity, the semi-enjoyable friendship—on which a finite life can come to grief.”

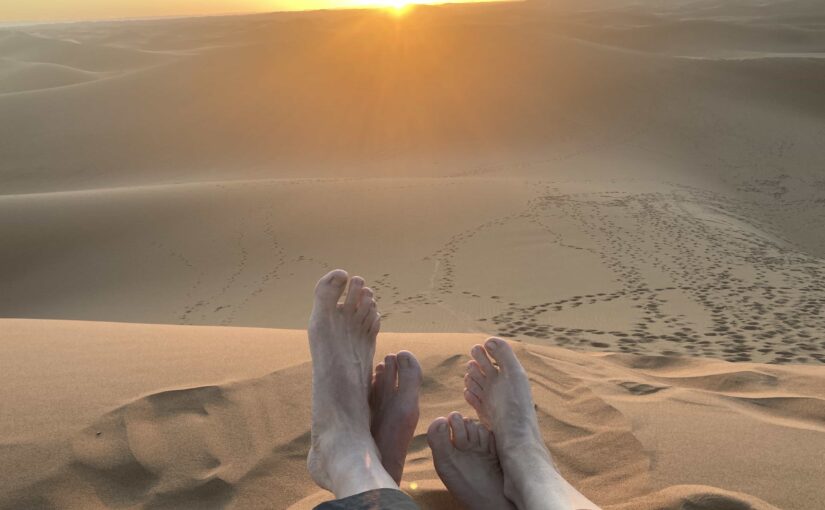

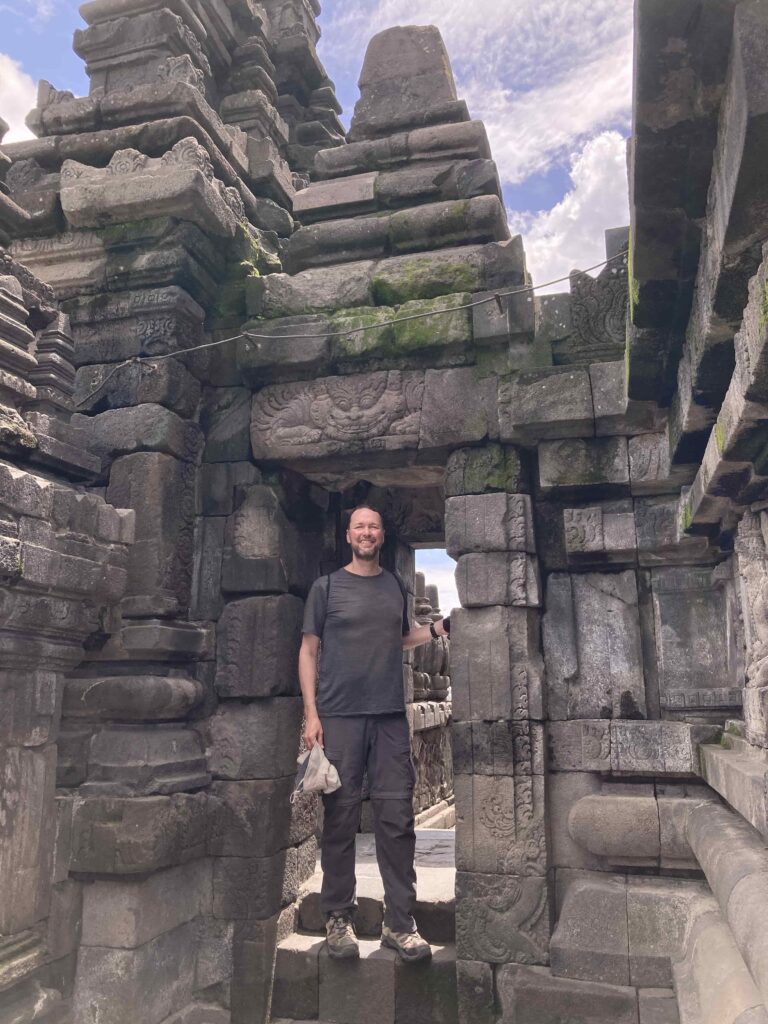

This concept was an eye-opening revelation for me. In order to focus on what I wanted to be and do the most, I needed to eliminate my lower priorities. In my case, that meant retiring my many appealing personas listed above, and focusing on the ones that are core for me: husband, father, friend, traveler, camper/hiker, personal finance coach, and lifelong student. Since one of my top priorities was to travel the world nomadically with just a carry-on and a backpack, I needed to do some major downsizing. I fully embraced minimalism with some surprising results.

But this downsizing is a lot easier said than done. For me, it was a long process. I truly enjoyed learning to play an instrument, gardening, and coaching soccer. To give up the things that went along with those pursuits wasn’t just getting rid of stuff I no longer valued. I was giving up valuable, but lower priority, pursuits that were preventing me from fully doing what I valued the most.

The hardest things for me to let go of were my electric guitar, amp, and case, the accessories of my dream of learning to play the guitar. I had wanted to play classic rock tunes around a campfire. On two separate occasions, I took weekly lessons for months on end. I practiced a lot, though not enough, since my identity as a musician wasn’t one of my top pursuits (and it had so much competition from my other middling-priority identities). During my second set of lessons, I spent over a $1,000 upgrading my $80 acoustic guitar for a new electric guitar and amp, thinking better equipment would help me learn quicker (it didn’t). I made small progress but not really enough to be satisfying.

After I stopped taking lessons and practicing, the new guitar remained a constant guilty reminder of the time and money I had sunk into learning to play. When I sold my (lightly used) electric guitar, amp, and case back to the music store I bought it from (at a fraction of the price), I felt free! I was giving myself permission to no longer strive to be a musician. I no longer had this physical reminder scolding me “You should practice music. Remember, it is the seventh most important thing you want to accomplish!” It was a conversation with stuff that I didn’t want to have any more.

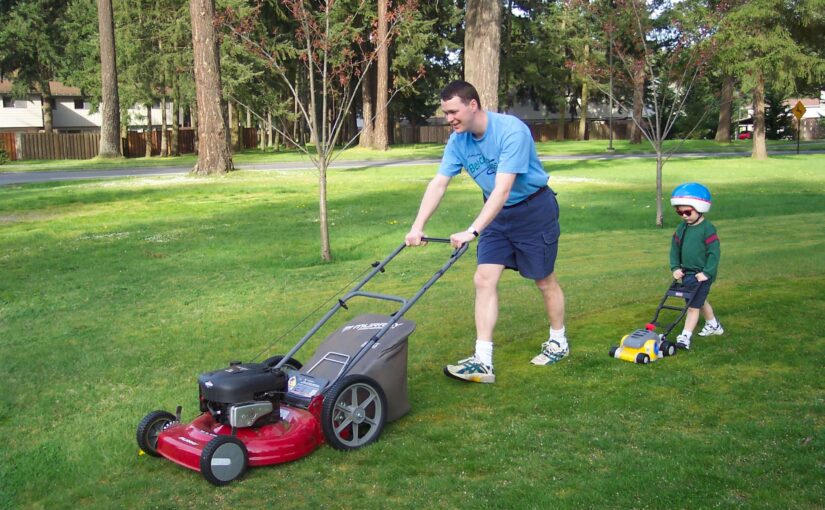

The time and money I spent trying to learn to play the guitar took time away from what I really wanted to do—read, travel, learn a language, and take better care of myself. Likewise, by getting rid of my canning equipment, lawn care equipment, tools, old files, old collections, job (I retired early), cars, and house, I released myself from numerous commitments and freed up enormous time and resources. (Asking myself tough questions helped me change my relationship with what I owned).

Because camping is one of my top priorities, I kept my camping gear (tent, sleeping bags, inflatable mattress, and cookware) neatly stored in my friend’s basement near Seattle. These possessions support my top values as each summer I return to the beautiful Pacific Northwest and enjoy weeks of camping among the evergreens.

Each person’s top priorities will likely be much different than mine, and of course top priorities can certainly change over time. When my life of traveling winds down, I may decide to return to a house and gardening or maybe pick up the harmonica.

It’s a useful exercise to distinguish your most important pursuits from the lower priority pursuits getting in your way. You may decide that learning a musical instrument is your top priority, so you’ll get that dusty guitar out of the basement and give it pride of place (and time and money) in your newly cleaned living space. You might ditch the tent that I decided to keep. The key is to hone in on your own top priorities, keep the few items that help you in those limited pursuits, and discard all the possessions that are part of lower-priority pursuits.

Having newfound time and resources to focus on world traveling, my relationships, reading, sleeping, stretching, and hiking has been amazing. I have traveled more this year (2024) than any other year. I have read more books this year than any other, including my years in college. I have spent more meaningful hours with my close family and friends than I had before embracing minimalism, because I had a clearer focus on why they were important to me. I walk and hike more than ever. I am constantly learning new things and tackling my foreign language proficiency goal.

I have swapped the elusive pursuit of happiness with the pursuit of contentment because I found that “enough” is fulfilling—enough in what I have, enough in what I do, and enough in who I am.

Doing fewer things better is…better! Removing the physical possessions around these lower-priority identities made it happen. By getting rid of these possessions, I gave myself permission to focus on the core of who I really wanted to be. Minimalism changed who I was.

[This post was republished on the minimalism and simple living website No Sidebar]