I once spent several hundred dollars on a high quality bike rack. It held four bikes, and there were four of us. It seemed like a great investment to increase our family biking time. But pretty quickly I found it was too unwieldy to use. I only used it twice and hated it both times. But instead of letting it go, I stored it and tripped over it in the basement for years even though I knew I would never use it again. I didn’t want to accept the sunk costs of this unfortunate purchase.

The sunk cost fallacy is our tendency to hold onto a purchase or continue with an endeavor we’ve invested money, effort, or time into—even if the current costs outweigh the benefits. I previously wrote about this business concept, but I wanted to expand on how this fallacy impacts what we personally own and why it can be difficult to let things go or do different things with our time. We should not allow the time or money we have previously invested to overly influence our future decisions about time and money.

We keep many things because we “paid good money” for them. I purchased the Seinfeld Series DVD box set for something like $120 when it first came out. Even though I made a digital copy of the show, I held onto the set because I believed I should get more than the garage sale price for it. But to recoup more I would need to take a nice photo, research what this item sold for recently ($25-$40), upload it onto a sales website, write a description, handle any inquiries, and then package it up and mail it to the purchaser. I might have made an additional $15-$30 (minus shipping) by doing all that, but I would never recover my $120 and I would end up sinking a lot of my time trying to get that money back. Instead, I accepted the sunk cost and put it in the garage sale—happy for someone to take it away for a few dollars.

Our possessions are most likely not worth near what we had paid for them in the store, and certainly not worth the extra resources required to recover the money sunk into them. I kept many things even though they were not a good fit, because honestly, I didn’t want to admit to my mistake and realize the loss by letting them go.

I have fallen into this fallacy on so many purchases. I can’t tell you all of the new or barely used items (clothes, cans of paints, collectibles, decor items, solvents, hardware, tools, kitchenware, and various other stuff) I kept only because I had sunk money into them and thought “someday” I could recover my investment. Once I accepted that they were expenses, not investments, and the money sunk into them was not coming back, it was easier to let them go.

The sunk cost fallacy often applies to non-refundable purchases. If we have non-refundable tickets to a show and then we miss the show at the last minute, the cost of that ticket is a sunk cost. But this sunk cost should not impact our decision whether we buy another ticket to the same show. I have to remind myself that purchases I made in the past should not prevent me from doing something different now or in the future, even if I can’t get my money back.

Sunk cost fallacy can apply to time, too.

The sunk cost fallacy can apply to things that we have sunk a lot of time into. Letting the sunk cost fallacy determine what we keep can negatively impact what we do with our time and add mental clutter. The weight of spending well over $1,000 on my electric guitar, amp, and hours of lessons was keeping me from moving on to higher priorities even though I knew I no longer prioritized learning to play the guitar.

I projected extra value on items that I spent a lot of time on. Items that I had frequently cleaned, maintained, organized, and stored assumed an extra weight of importance since I sunk my time into them. Our old board games that I loved playing like King Oil and Careers were not any more valuable because I had spent hours playing them in my childhood. The same goes for my old kitchenware, musical instruments, college papers, CDs and DVDs. This applies to projects as well. If it is time to sell our house, I shouldn’t let my time spent on numerous home projects and memories of raising our family there keep us in a house that no longer meets our needs today or in the future.

Look out for sunk cost fallacy’s cousin, the endowment effect.

A related issue is the Endowment Effect, when we value things more just because we own them. We endow our physical possessions with extra value and meaning that we wouldn’t apply to the same items that we didn’t own. We keep many items just because they are ours. I had a lot of clothes like this.

To help me overcome this effect, I had to ask myself if I would pay money to buy that same item again. If this exact shirt was for sale at a store, would I buy it? When I realized that I wouldn’t, it made it easier to donate them. Just because we own it, doesn’t make something more valuable.

Avoid doubling down on bad decisions.

The sunk cost fallacy took control of my decisions when I made one of my worst investing mistakes—purchasing Boston Chicken stock.

In 1997, I purchased 1,000 shares of Boston Chicken (later known as Boston Market). Unfortunately, the company was cooking more than delicious chicken. Just weeks before I purchased the stock (and unbeknownst to me), the company revealed it was recycling money by loaning to its franchisees to build new restaurants, masking its true, troubling financial picture—huge debt.

Boston Chicken soon filed for bankruptcy. I quickly understood that I had made a bad investment decision, but I was afraid to sell and lock in my losses. By letting my desire to recoup my initial investment (at this point a sunk cost) drive my decision, I experienced even greater losses. I watched that stock drop from around $5 per share to pennies as the company financially collapsed. By repeatedly not selling week after week as it plummeted, I let my sunk cost from one bad decision drive more bad decisions.

If we make a bad decision, understanding the sunk cost fallacy helps to see it for what it is, own the mistake and get out of it, resisting the urge to double-down because of a fear of losing what we have invested so far. We should cut our losses and redirect our future resources to something better.

Even good decisions can become susceptible to the sunk cost fallacy.

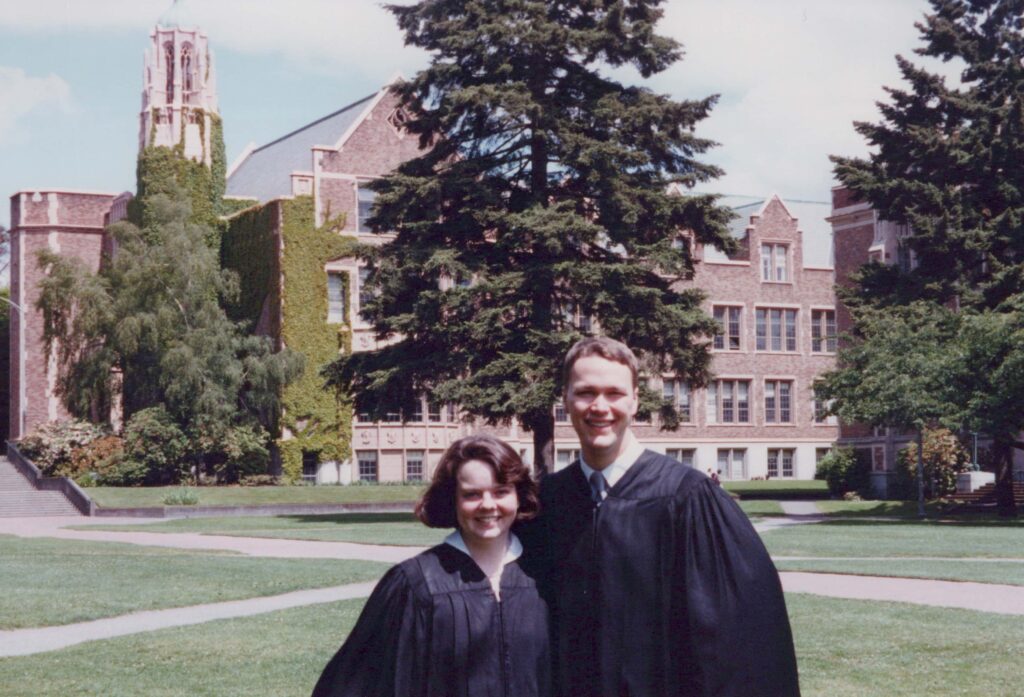

Sometimes decisions are good in the moment, but they can trap us in the sunk cost fallacy later. For example many of us, me included, earned a degree in a field that we didn’t end up working in (mine was history). Spending money and time getting a particular degree is a sunk cost. If the job opportunities that present themselves are in different fields or we decide we want to do something different, we should not let those sunk educational costs prevent us from going in a different direction.

I was able to set aside the weight of my sunk costs (time, knowledge, and commitment to the organization) and quit my dream job to instead pursue what I valued more—travel, more quality time with family and friends, my health, and following my curiosities to include learning more about human history.

Decisions in the past, even good ones, that we put a lot of money and time into can sometimes cause us to limit our options. We need to recognize that these are sunk costs and consider other opportunities even if it means setting these previous investments aside.

Is there something you’re currently keeping or spending time on, and you’re doing so because of the time or money you already have invested? If so, consider stepping back and evaluating if sunk cost fallacy is preventing you from decluttering or managing your time. Recognize that the time and money already spent is gone, but we can make a fresh start with how we spend these valuable resources going forward.

Thanks for reading! If you would like to be notified of new posts or updates from Living The FIgh Life, please subscribe below. I am an inconsistent blogger (hey, I'm retired!) so this is the best way to be notified of new content. Cheers!

![]()