I have noticed a trend in personal finance circles distorting the concept of the “latté factor” which I mentioned in my article “Has the FIRE Movement Lost Its Way?” but I believe needs to be addressed directly.

As a quick primer, the latté factor was made popular by personal finance author David Bach in his book The Latté Factor. In basic terms he outlines the latté factor as changing our spending behavior on small frequent purchases like a daily coffee and instead investing that money. By doing so, these small savings will add up over time and make a difference in our financial future through the power of compounding. But his book is definitely not just about coffee. It is about controlling all of the seemingly small frequent purchases in order to buy your financial freedom—true control of your time and resources.

However, on recent personal finance podcasts and in blogs, hosts and guests are frequently saying that you don’t need to give up your daily coffee to achieve financial independence. For example, on a recent back-to-basics episode of ChooseFI (one of my favorite personal finance podcasts), host Brad Barrett and his guest Jackie Cummings Koski discuss the importance of frugality. While they talked about “the value of small changes” by saving money on subscriptions, cell-phone plans, and insurance, they gave a pass to buying a daily latté. “If you need your coffee, then you should buy that,” Brad says. Why not save on coffee too? I suspect it may have something to do with financial author Ramit Sethi’s strong stance against cutting out lattés, which Brad has mentioned in the past.

Advice to reduce monthly cell phone bills but give a pass to daily latté purchases sends a confusing message to those trying to establish good spending habits. Making frugal decisions in the pursuit of financial independence includes examining all of our small (and large) habitual purchases, especially those that could be replicated in a more affordable way, like our daily coffee purchases. Here are my 4 reasons why our daily coffee purchase should be included in back-to-basics money advice.

Reason 1: You don’t have to give up your daily quality coffee.

This is probably the biggest distortion. Not paying $5.50 a day for coffee does not mean we can’t get our coffee fix. We can make a fabulous cup of coffee at home for a lot less and in the same or less amount of time than buying a coffee out. This includes a quality coffee maker, good beans, your favorite milk, and any specialty seasonings you like. (When thinking about time spent buying a coffee out—driving there, ordering, waiting, and driving on—don’t forget to count the time you spend at work making the extra after-tax money to pay for it).

Reason 2: Forgoing small habitual spending matters to financial success.

Does replacing our daily latté purchase with a homebrew matter to our financial success? Yes! As outlined in this article from The Perky Kitchen blog, we can save ~$4.30 on each latte we make at home (the author included the cost for a latté machine depreciated over 3 years—a conservative estimate). Since coffee is almost always a daily habit (thanks caffeine), avoiding paying $5.50 per cup 24 times in a month and paying $1.20 instead will reduce monthly expenses by $100 ($130 if it is truly a daily buy-out habit) AND we still get to have a delicious cup of custom made coffee at home! The elusive win-win.

In the aforementioned ChooseFI episode, Brad explained that reducing expenses by $100 a month reduces our financial independence number by $30K! And, by investing that money over 20 years at an 8% average return will add $60K to your net worth—a $90K swing! Yeah, it matters!

Reason 3: More important than saving money is positively changing our financial habits.

You might be asking, why are you picking on coffee, anyway? Simply put, coffee provides a great example for controlling spending—it is popular (i.e., applies to most people), it is usually a daily morning habit, it is often bought out, and while it seems like an insignificant expenditure, it quickly adds up. But most importantly, it is a habit that hits early in the day, setting the tone for the rest of the day. By making our coffee at home, we are making a positive financial decision first thing in the morning, powerfully reinforcing our goal of financial freedom. By starting our day off on the right foot, we set ourselves up for other positive financial decisions later. More important than the actual monetary savings is the positive change to our financial habits—good habits are powerful!

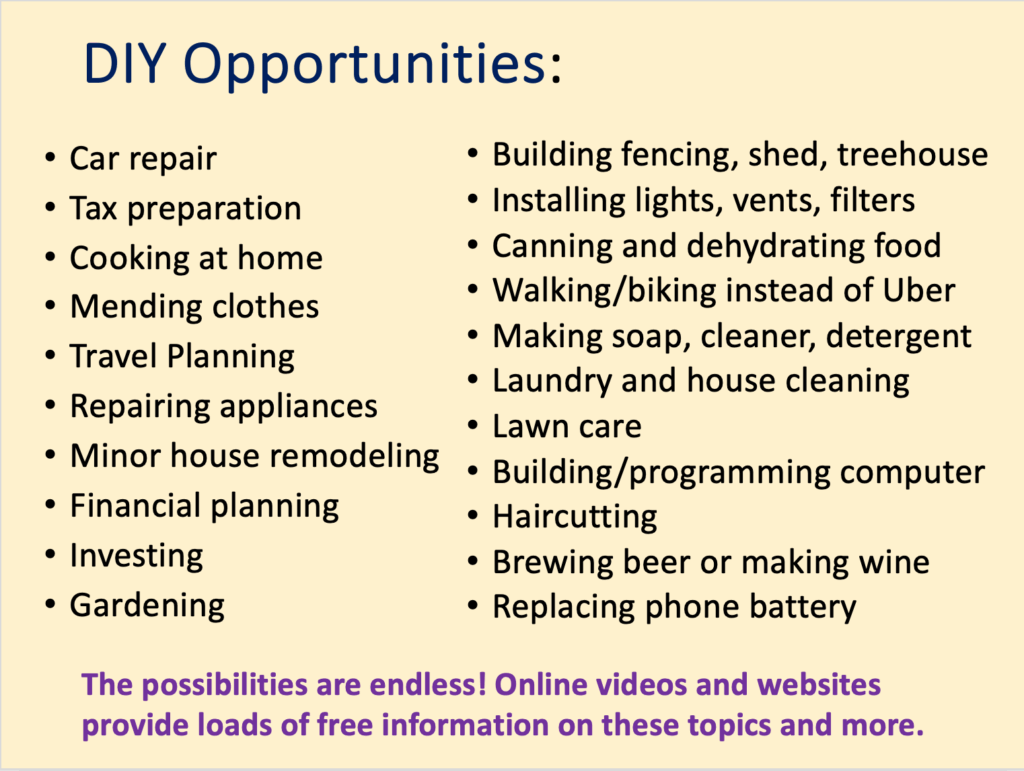

It is definitely not just about coffee. We need to examine all areas of spending, large and small, where we make financial decisions out of habit or without thinking about their impact on our overall budget. Doing so will help us identify areas where we can implement positive financial habits.

Reason 4: Making your own coffee builds skills, self-reliance, and self-confidence.

Skills are assets! Making a quality latté is a skill. Doing foam art is a skill. When we do things for ourselves we learn new skills and accomplish things which in turn builds our self-reliance and self-confidence. This self-confidence helps us tackle bigger projects which instill more self confidence and sense of accomplishment—a virtuous cycle.

My 25 year-old son is a great example. About a year ago, he started drinking coffee on a regular basis. Instead of joining the crowds at Starbucks each morning, he taught himself about coffee. He learned about quality beans, roasting techniques, grinding, and how to make espressos, cappuccinos, and lattés. He invested in a high-quality at-home espresso machine, and found a local roaster that he likes. He not only has an exceptional cup of coffee every morning for a fraction of the long-term costs, he has coffee skills. He can converse deeply with fellow coffee nerds and offer his guests an exceptional custom-made cup of joe complete with foam art. Now instead of heading to the coffee shop when we visit, my wife and I enjoy a relaxing morning at his place.

My son enjoying his high-quality cup of coffee at home (complete with foam art)

Making our own coffee is empowering, as is making our own lunch and hosting friends for a drink on our patio. I offer some examples from my life on how I am able to get the same basic goods or services for a lot less money in this article on how frugality made my life happier.

Some final thoughts.

Making coffee at home or any frugal practice isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition. We can still meet a friend at a coffee shop for a coffee (and confirm if your home brew skills are outpacing the competition), or have a drink out, or eat out occasionally. A single $5.50 expense won’t break the budget and an occasional break from the routine won’t destroy our good financial habits. In many cases, we will be reminded that our coffee and cooking is better anyway. I have learned that it is not spending more that makes me happier and more content, it is primarily spending quality time with my family and friends, time in nature, learning, and taking care of my health that brings the most happiness—all of which can be done without spending a lot more money.

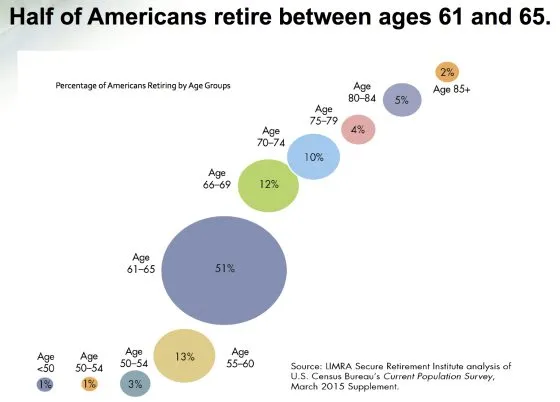

The latté factor is most important when you are starting on your financial journey.The financial experts who disregard the latté factor may have forgotten what it is like to get started on the road to financial freedom. Ramit Sethi’s advice to just put away 10-20 percent of your money into savings first and then not worry about how you spend the rest (to include your daily latté if that is your desire) breaks down under scrutiny. For people living paycheck-to-paycheck, there isn’t 10% readily available. In many cases people are paying off credit card debt trying to get back to zero. Investing a thousand dollars in the stock market making 12% is a losing battle against carrying a thousand dollar credit card balance at 23% interest. Financial advice needs to meet people where they are!

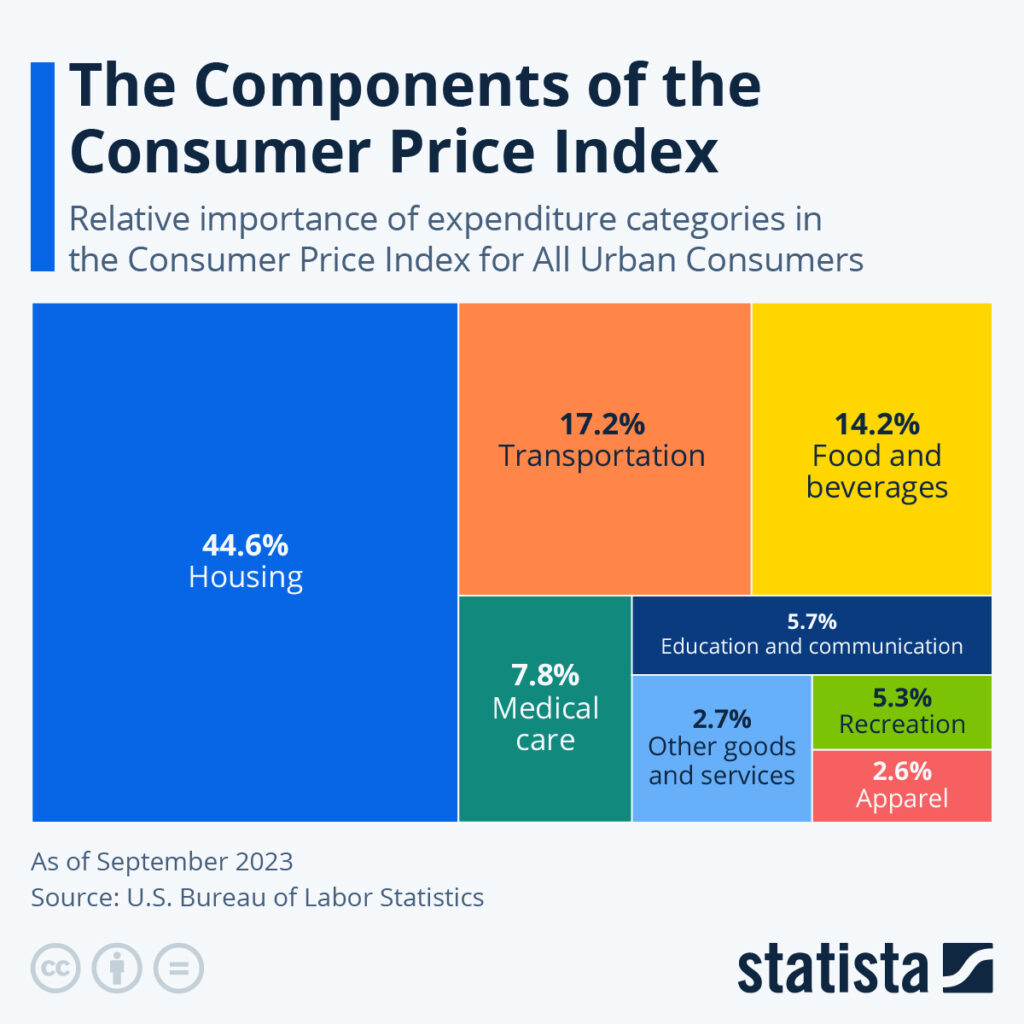

Ramit also advises to focus on the big expenses like housing, cars, and education expenses. To make any progress, we have to spend less than we earn. Day one of our new financial life starts with controlling our spending. The first thing we purchase is likely our morning coffee. Of course, we also need to look at our big expenses like housing, transportation, and food, but $100 in coffee spending each month matters, as does spending on subscriptions, drinks out, etc. It’s not big expenditures or small ones—it’s both. But it usually starts with controlling the small habitual purchases and freeing up those 5s, 10s, and 100s in the budget which can quickly add up.

After we have our consumer debt paid off, a solid emergency fund, a sizable amount in investments and strong financial habits in place, then we can worry a bit less about the smaller purchases. They become less and less material the stronger our financial picture grows. At that point, we can buy out our coffee every day if we want to…but will we want to? When we’ve got a system for great coffee at home?

Let’s not ignore or distort the power of the latté factor when we are talking back-to-basics of personal finance. Coffee anyone?