Wouldn’t it be great if we had a machine that would save us the trouble of hanging up our clothes on a line to dry? No more waiting numerous hours, often overnight, before the clothes are dry and ready to fold and put away?

We could save that time with the right machine. All we’d have to do is take the bundle of wet clothes from the washing machine and plop it into this brilliant new machine, scrape out a small sock’s worth of lint from the previous load, close the door, choose from 12+ settings, and press start.

Dried clothes in 40 minutes—hot dog!

Well, that’s after I separated my cottons from my synthetics, from my delicates, from my (hypothetical) cashmere (which I have to line dry anyway). So they all couldn’t dry at the same time. But still…amazing idea, right?

I would need to drop $700 on this new-fangled machine and spend another $525-$750 annually on electricity. Plus an average of ~$60 per year on repairs, and then buy a replacement machine in 10-13 years. But what else would I do with $730 a year? At the average American’s $24 per hour net wage, that is only 30 hours of extra work per year—just 35 minutes per week. Nothing…right? Have I mentioned I would save 20 minutes hanging up my clothes to dry each week?

Don’t forget I would need to purchase replacement clothes much more frequently as that large clump of lint each load takes its toll—clothing fibers break down more quickly and my clothes get holes more quickly. But hey, that’s a great excuse to buy new stuff!

And I haven’t mentioned yet the ecological impact of building the machine, generating the electricity, and making the extra replacement clothing. But what would my kids and grandkids want with all those natural resources anyway? I saved 20 minutes!

Well, maybe electric clothes dryers aren’t the indispensable appliances of modern households I thought they were. The “convenience” they deliver comes at a high price—tyranny of convenience. But it’s not just dryers.

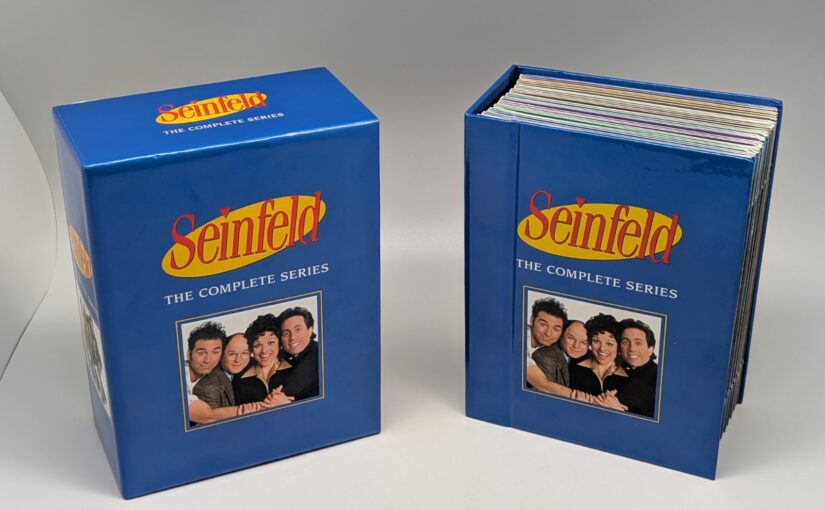

Over the decades we have been sold machine after machine with the promise to make our lives more convenient. From washers and dryers, to dishwashers, to microwaves, to cell phones, to robot vacuums. We’ve also been sold service after service, such as next-day (hour?) shopping delivery, food delivery, instant communication, music and entertainment services, and on and on.

Most conveniences come with a price. They often cost more money, but also cost us in terms of what we value—time, contentment, happiness, environmental impacts, self-reliance, and in-person human interactions.

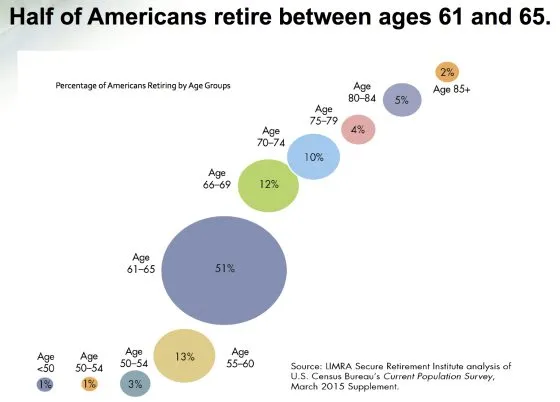

Were we less happy in the 70’s before microwaves? Or in the 00’s before smartphones were in every pocket? We didn’t become less busy people with the addition of each convenience. How much of our newly freed-up time was spent earning the money to pay for these conveniences?

Do we work fewer hours now that we have a computer on every desk? I certainly didn’t, but instead of talking with people in person, I wrote and responded to emails. The convenience of my computer and email was at the cost of direct human interaction. The job still got done, but it was far less enjoyable.

So many aspects of our lives are driven by the allure of convenience, but at what cost?

Does online shopping save us time and money? Or do we actually buy more than we need on high-interest credit cards because it is so convenient?

Are the 15 minutes we save from picking-up our food from the restaurant worth the extra hour we have to work to pay for it? Is it worth the lukewarm and soggy product we so often receive?

Conveniences often cost us more than we realize—a Faustian bargain.

“Faustian bargains are by their nature tragic or self-defeating for the person who makes them, because what is surrendered is ultimately far more valuable than what is obtained, whether or not the bargainer appreciates that fact.” — Encyclopedia Britannica (online)

Many conveniences cost more than the alternative, thereby requiring us to work longer hours to pay for them. Like my clothes dryer and food delivery examples, we try to buy back time by hiring a house cleaner or lawn service but often wind up working more hours to pay for it than the time we saved.

Many conveniences erode our self-sufficiency. Cooking, for example, is an important life skill. The convenience of eating out or buying preprepared, precooked, precut, preseasoned and prepackaged usually costs more, is often less healthy, and degrades our ability to nourish ourselves. This can be applied to laundry, cleaning, delivery, repairs, etc. Skills are assets and self-sufficiency builds our self-confidence.

Most take more resources to produce or deliver. Just drying my clothes on a simple clothesline, for example, takes far fewer of our Earth’s resources than a clothes dryer.

Many reduce our in-person human connections. We text instead of calling. We post instead of getting together in-person.

Some are actually inconvenient. Having my dentist, plumber, bank, and every business I have ever been a customer with (and many I haven’t), send me a DM or email to my phone at any time is very inconvenient.

Conveniences can also expose us to a litany of choices, which brings me to the tyranny of convenience’s evil step-sister…

The Tyranny of Choice

The convenience of having unlimited choices with convenient services such as Spotify, Amazon Prime, and food delivery services introduces the tyranny of choice where some options are good, but nearly unlimited options actually reduce our happiness. We want to listen to the perfect song, find the perfect movie for tonight, or eat something really delicious. And so we spend hours researching through endless options, weighing reviews, and comparing choices only to be less happy because our expectations were so high (it got a 4.8 with 389 reviews, so it must be great, right?). Analysis paralysis—ugh!

With so many choices in daily life, I find myself wanting fewer choices. I am happier when I have fewer media choices, when a menu has only 10 items, when a flight only has only 10-15 movies instead of 200. The more opportunities that confront us, the more opportunity costs we perceive in comparison to the choice we actually make and the less happy we tend to be with our choice (Scientific American, Dec 1, 2004).

Thinking about the conveniences we use.

Not all conveniences are problematic, and there are some ways to mitigate their negative impacts. Some save money and time and make life better and easier. Which conveniences are worth it and which ones are not will vary for each person. For me, a vacuum cleaner cleans my rugs and carpet better and quicker than I could without it, but I value the cost savings, self-reliance, and self-confidence I get from repairing my vacuum cleaner myself.

What I am suggesting is that we think about the conveniences that we rely on and evaluate them for how much they are truly adding to our lives. Then weighing that against how much they might be subtracting in costs (and hours needed to earn that money) as well as social, environmental, and other impacts.

I am not a fan of crunchy towels, but the costs of a clothes dryer far outweigh any benefits for me.