Becoming a minimalist takes a lot of introspection. Identifying what you value the very most and letting go of the rest is hard work. Asking yourself tough questions to separate the objects you own from the emotions, marketing pressures, perceived value, and other forces that drive what we buy and own. Likewise, I’ve found that staying a minimalist doesn’t happen on its own––I have to stay focused on my values to avoid falling back into the collect-purge cycle.

For decades I spent countless hours each year organizing, culling, and disposing of (selling in a garage sale or donating) loads of excess stuff that had accumulated since the last purge. Then I’d rinse and repeat the following year. My master organizing or annual spring cleaning efforts didn’t make me a minimalist, but changing my relationship with stuff did. I became a minimalist in March of 2022––about 15 months before my wife and I downsized 98% of our physical possessions and became full-time nomads.

But how do we maintain our newfound freedom? By setting up systems and methods to prevent new items from re-filling the spaces we have worked so hard to empty. Here are my strategies for how I remain a minimalist and guard my metaphorical “front gate” preventing unwanted stuff from creeping back into my life.

I stopped shopping.

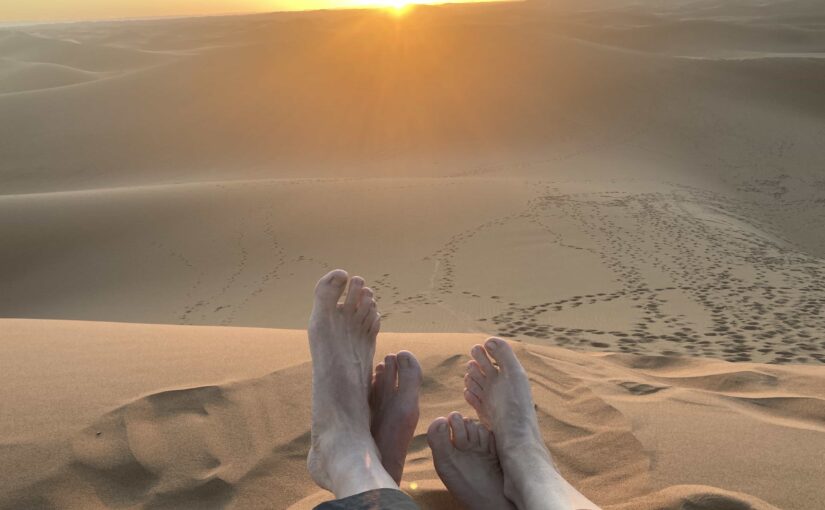

Shopping as entertainment is no longer a part of my life. Sure, I still buy an item like a shirt or shoes when I need to, but I don’t browse just to see what savvy marketers are trying to get me to buy. Instead I read, visit museums, enjoy lengthy nature walks, and lots more. There is so much to do and see without needing to go into a mall, big box store, or antique shop for entertainment. As I travel full-time, I am constantly confronted with shopping opportunities. So many museums, amusement rides, and other tourist sites channel me into their gift shops in hopes I will leave with some trinkets, whether lovely hand-crafted local items or lower-quality items imported from elsewhere. I am barraged at airports, along the streets of quaint downtowns, and sometimes on trains and buses. When a market of locally produced crafts is integrated into a historic street or festival (which is frequent), I stroll, hands behind my back, and admire their handy work––but I keep moving, looking for the food or drink stalls with a delicious local flavor to enjoy instead. Grilled corn is a favorite of mine. As I encounter the various shopping situations around the world, I remind myself of my values and buy only things that support them closely. My souvenirs are my photos and memories made, which are easily portable and I can enjoy their dividends anywhere, again and again.

I shared my minimalist values with family, friends and co-workers.

Gift giving is ingrained in our society. I enjoy giving gifts, so I can’t expect my friends and family to refrain from giving me gifts. I do politely let relatives and friends know I value experiences (eating out, visiting a museum, and travel) and consumables (homemade cookies or a bottle of craft gin) over physical possessions. I let them know about my efforts to downsize and that I value having less physical things in my life. If asked what I would like for my birthday or Christmas I no longer give the modest “oh, you don’t have to give me anything” non-answer. Instead, I help them by giving options: a gift card to a favorite restaurant, tickets to a museum, concert or sporting event, their famous pineapple upside down cake, or even something physical that I truly do need at that moment like a replacement shirt. I also model my values by giving gifts that are experiences and consumables unless I know exactly what physical object they need. While I have received a couple of gifts over the last few years where I needed to find them a new home, overall my family and friends have been gracious in recognizing and supporting my minimalist values with their gift giving.

I’m armed with responses to help turn down unwanted gifts.

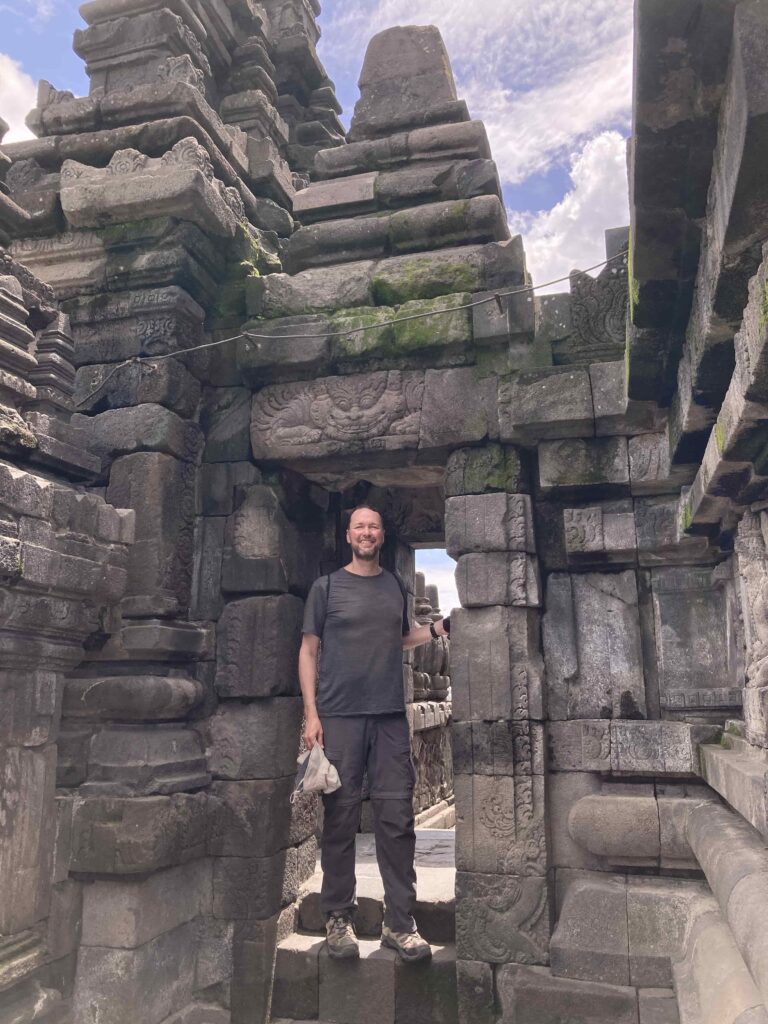

As my wife and I travel, well meaning people offer us gifts. Our hiking guide to the top of Mount Fansipan surprised us with commemorative medals for completing the tough hike to the top of Vietnam’s highest peak. We thanked him profusely for carrying them up the mountain on our behalf, took a picture with them, and then politely returned the medals letting him know that “We travel light,” and “Sorry, we have very small suitcases,” and asking if the still-new medals could be given to other hikers. He totally understood and returned them to his backpack for the next hikers he guided up the mountain. In addition to a persistent “no thank you,” these simple phrases have helped us avoid most offered gifts. Giving a simple reason for why I am unable to accept an unwanted gift often helps the gift-giver accept my choice to pass on the gift.

I don’t let unwanted objects enter my daily routine.

For gifts of physical objects that I can’t dissuade someone from giving, I quickly find a new home for them and don’t let them become a part of my life. Just because someone gave me something does not mean I have to imbue it with emotion and sentiment. Their love for me, and mine for them, are separate from the gift itself. It is the thought that counts, not the physical object. For Christmas last year I was given a ball cap with one of my favorite college team’s logo on it. I enjoy watching that team play, but I don’t wear ball caps. But a close friend who loves that team and wears ball caps was happy to have it.

I’m wary of accepting gift bags or other “freebies.” While free stuff often feels like getting value and speaks to that inner poor college student in me, it usually doesn’t align with my top values and can quickly take up valuable space in my life. Freebies are never truly free as every object we own comes with an IOU of effort to organize, clean, and eventually dispose of it. At a recent personal finance conference I attended, I let them know in advance that I didn’t need the conference T-shirt even though it was included in the registration. Even though it was a fun T-shirt for an organization I support, I just didn’t need it. We can turn down freebies and not allow them to re-clutter our lives.

This applies to things we buy that for one reason or another don’t work as well as we thought. Finding the right clothes for full-time travel took some calibrating. For example, I replaced two cotton shirts (my long-time preference) with quick-dry synthetic shirts that I thought would travel better. But I quickly learned that merino wool shirts were the best travel clothes for me. So instead of letting the two nearly new synthetic shirts take up space in my suitcase or storage, I donated them. I saved space, both physical and mental, and let someone else find value in them.

I recognize marketing strategies and resist them.

Don’t “collect all five!” And a diamond bracelet isn’t actually the only way to express devotion to a significant other. We are barraged by clever and powerful marketing tactics designed to make us feel like we have to own a product to be part of the crowd, feel complete, or avoid missing out. Recognizing these forces can help us build our immunity to them. When dumped into a gift shop after visiting a tourist attraction, I remind myself that this is by design, and that I am not obligated to look at their wares let alone buy anything. I don’t linger, I head for the exit as planned, and I enjoy the next part of my day.

This goes for online marking strategies, too. Minimizing our exposure to ads will help us resist buying stuff we don’t need. I recommend using an ad blocker on your browser. When Google stopped supporting the uBlock Origin extension, I switched to Firefox (which offers more privacy anyway). I switched from Google search to DuckDuckGo and I get a lot less ads. I also use a VPN with an ad blocker. Bottom line––using ad blockers really helps!

Guarding the gate requires some vigilance. But having systems in place to reduce exposure to our buy-buy-buy culture, declining gifts or steering potential gift givers toward what you value most, and not letting unwanted new items enter our daily routine can avoid the life-consuming collect-purge cycle and support a life of contentment. With some proactive strategies, we can maintain and continue to reap the life-changing benefits of the minimalist life.